The individual isn't what it used to be

Tim Waring thinks human evolution is shifting from genetic and individual to cultural and collective

Many of us experience a kind of horror at the thought of losing ourselves. The primary antagonist of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Voyager is a hive mind called the Borg that assimilates any individual living things or technologies it comes in contact with into its Collective. They're like space ants, complete with a queen — except if ants could turn their prey into fellow ants rather than just eating it. The moral of the Borg arc is essentially that the homogenous collective degrades the whole and that diversity and individuality are worth fighting for. Resistance is not futile.

On the other hand, I'd argue there are strains of ascendant politics that clearly reflect some kind of anti-individual longing be subsumed in some grand collective project that goes far beyond the self. Less dramatically, a certain degree of willingness to make personal sacrifices for one's community — and not just blood-relatives — is generally seen as morally good. Loss of self or ego death is a common experience reported by people who take psychedelic drugs; melting into the universe is either terrifying or euphoric or both, depending who you ask. We humans seem to have an ambivalent relationship to the idea of being part of a greater whole: fear and longing all at once.

Perhaps that's what you'd expect from a species of individuals on the road to becoming collectives.

Tim Waring, an ecologist studying anthropology in the economics department at the University of Maine, thinks we are such a species. For several decades he's studied how culture and genetics interact to shape human evolution and has concluded that our species is in the middle of an evolutionary transition in individuality — a shift, like the jump from single cells to multicellular animals, in what counts as a biological individual. And he's eager to move the conversation past sci-fi speculation (sorry, Tim, I couldn't resist opening with the Borg) and into the realm of testable theory.

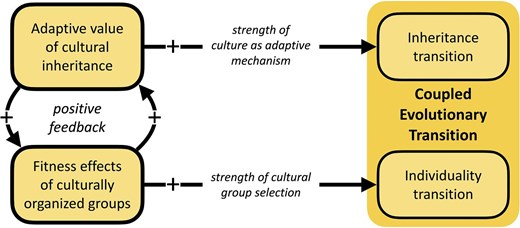

In a recent paper, Tim and his colleague Zachary Wood outlined a theoretical framework for a human evolutionary transition in individuality that they think could cut a path towards concrete predictions and empirical tests of the hypothesis. Their core insight was to identify two distinct forces that, operating in parallel, could trigger a positive feedback loop that accelerates our species towards a new collective existence in which culture, not genes, is the most important information passed down the generations. These forces are: 1) the degree to which cultural adaptation influences fitness more than genetic adaptation, and 2) the degree to which an individual's fitness is determined by the group she belongs to rather than her own characteristics. Based on this simple framework, Tim and Zach make several predictions about what we could expect from our species if we really are undergoing this kind of dual transition from individuals under Darwinian selection on genes to groups under selection on cultural traits. In the near future, Tim plans to test some of them against real-world data — an important step if this field is going to move from philosophy of biology circles into more empirical ones.

I spoke with Tim about cultural evolution, transitions in individuality, the politics of human evolutionary history — and, yes, why it might not be so bad to become the Borg.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get interested in cultural evolution?

As an undergrad in the late 90s, I became obsessed with the evolution of culture and the way in which it explains the out of control nature of society and human behavior. After college in the early 2000s, I came across the idea of memes from Richard Dawkins' 1976 book The Selfish Gene. Dawkins coined the term "meme" — a replicating unit of culture as contrasted to a gene as a replicating unit of nucleic acid. To me, this unlocked something important. If culture changes and diversifies in quasi-Darwinian ways, then cultural evolution might be the key to understand the out-of-control nature of human change.

What do you mean by human nature and society being "out of control?"

I mean this sort of escalating process of technological evolution and the explosive growth of human groups. At the scale of a human lifespan, it's easy to be convinced that things are somewhat stable — that the fact that our population has exploded and the world has changed dramatically is somehow not a huge exclamation point. That's a perspective I think is deeply wrong.

Let's focus in on the specific kind of transition that you think is happening in our species. What, exactly, is an evolutionary transition in individuality?

The major evolutionary transitions concept that John Maynard Smith and Eörs Szathmáry first proposed in 1995 describes step changes in the evolution of complexity. They include a set of criteria including the emergence of centralized control, strong division of labor between component parts, and changes to the way that adaptive information is inherited.

That early framework included a number of things like the emergence of sexual reproduction. Evolutionary transitions in individuality is a sharper concept: it specifically talks about a change in which a set of individual, free living organisms form groups. Those groups eventually become entirely dependent upon each other, and then finally through an escalating process of group selection, they come to reproduce as groups.

Ant colonies come to mind.

Yes. The canonical examples include things like the evolution of the eukaryotic cell from symbiotic prokaryotic cells that became organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts. Another example is the emergence of multicellularity. Multicellularity has likely emerged numerous times, in many different lineages. And another example that is very useful when we're thinking of comparisons with humans, is, of course, the eusocial and colonial insects such as ants and termites.

Those are all pretty dramatic transitions! But is there really a case to be made that we're becoming ants when it's the individual and not the group that receives rights and responsibilities in many societies? Individuals pay taxes, not kinship groups.

You're right about the individual being seeing as the fundamental unit of society, especially in the West. But there are notable differences in how societies think about the role of the individual versus the role of the group. Also even in the Western tradition, scholars and social scientists have been fascinated by group-level dynamics in a number of ways. In 1651 Thomas Hobbes proposed his concept of the Leviathan, which is the idea of a king operating almost as the mind of a super-organism that is society. Even Adam Smith, who had a very individualistic perspective, nonetheless had a strong point about how individual action creates a group-level benefit.

So, what's the evidence that we're going through a transition in individuality?

Well, the evidence is all around us! You can think about two major patterns in life: the importance of group structure and the relative importance of cultural inheritance in comparison to genetic inheritance.

Since the emergence of our species in Eastern Africa, we have seen a massive explosion in the size, complexity, and capacity of groups. We have an immense division of labor today. We have estimates are between 10,000 and 500,000 different types of jobs on planet. It's gone well beyond just acquiring cultural adaptive strategies and knowledge and skills — we also are deeply dependent on group-level infrastructure which is designed and maintained by group-level cultural organization. And our groups are often centralized, and have hierarchical structure. In a nutshell, our species is not only "culturally obligate," but also deeply and increasingly dependent on culturally organized groups.

Other changes happening too, even including in the way that biological reproduction happens. For instance, a large number of humans give birth in hospitals and this increases our ability to survive during childbirth, which is excellent. And we have a set of very novel ways to enhance our likelihood of being able to reproduce. We have in vitro fertilization. We have sperm donors. We have egg donors. We have surrogate mothers. Of course, this also means that over generations we come to depend on reproductive medicine more and more, as we should expect. Patterns of genetic descent are changing.

You've been working on making this story concrete enough to start building models that could make more concrete predictions about what you'd expect from our species if cultural change really is overtaking genetic evolution. What does that look like?

We are putting together a full theory of an evolutionary transition in humans. The key insight is that the transition is a two-dimensional process. To take a step back for a second: people who study cultural evolution have long been aware that culture is an adaptive stream of information akin to, but different from genetic inheritance. Evolutionary anthropologists have suggested that the emergence of group structure in human society is a signal of some sort of evolutionary transition. But biologists argue that an evolutionary transition in individuality cannot happening in humans because human groups are increasingly intermixed genetically. In order to have a genetic evolutionary transition, we need strongly defined genetic groups. And the biologists are right. The key point is to not only bring these two pieces together, but to show how they interlock.

How do you reconcile those two observations: that human culture is clearly inherited, but groups are becoming more genetically intermixed?

We humans are not experiencing a genetic transition in individuality. Instead, we're experiencing a transition in inheritance from genes to culture, where the primary mode of adaptation shifts slowly from genetic adaptation to cultural learning, eventually to the point of deep dependence on inherited cultural information. And the thing is, cultural information tends to be group-structured. That's part of one of its unique strengths — it can solve group-level problems really effectively. So the idea here, the core nugget, is that humans are experiencing a transition in inheritance and in individuality at the same time. The core requirement for this is simply that cultural evolution is more rapid or adaptive than genetic evolution, and that it is more group-structured. Putting all of those pieces together, along with the evidence and suggesting how to test the predictions of this framework is what's novel here.

Are there other examples from biology of transitions in inheritance? It seems like DNA has ruled supreme for a while.

It's generally believed that RNA preceded DNA. But now DNA sits in the in the queen's throne and gives information to RNA, and RNA conveys that information to ribosomes. There was a transition in the sort of primary repository of long term adaptive information storage. That's the best example of a really broad and deep transition in inheritance. But we are beginning to realize that there multiple or even many types of inheritance that matter. Environmental inheritance is one of them. Right? Another one is the gut microbiome. Understanding how adaptive fitness-conferring information accumulates and dissipates across these inheritance systems is a new stream of evolutionary research.

It strikes me as obvious and intuitive that the most important heritable information for humans is culture, rather than genes: if you plopped me in the Arctic, picking up cultural adaptations would allow me to survive immediately.

To put a point on it: if you look at human expansion across the planet over the last 80,000 years, what you see is not a pattern of genetic adaptive radiation. There are some genetic changes as we go to different extremes. But mostly what you see is a giant amount of adaptive radiation in tool kits and social technology and hunting and foraging strategies. It's very clear that we adapt culturally to novel environments far more than we adapt genetically.

What's less intuitive to me is what the unit of selection is in cultural evolution, is it individuals or groups?

That’s a good question! The idea here is that the unit of selection in cultural evolution may be changing. Of course, socially learned behavior and beliefs influence individual human life outcomes. So individual humans are a relevant unit of selection. But the cultural practices, capacities, and institutions of human groups also matter. What’s more, large and complex groups have more information than an individual can use. For example, I might specialize in doing my science, but I'm not super great at running a business or doing agriculture. This is what Joseph Henrich and Michael Muthukrishna described as a collective brain. The more brains you have, the more the group can remember. So that means you can have more roles, and those roles can subdivide tasks more effectively, and your productivity per capita can be higher. You also have greater problem solving ability when you have more brains. This pattern has been shown again and again in economics: larger groups are more creative per capita. So, as population density goes up, the number of patents per person goes up. We are smarter in larger groups. This means that groups that figure out how to deploy their brains most productively and creatively may fare better. Therefore, human groups, rather than individuals, are increasingly becoming a unit of selection for cultural evolution.

But do groups also reproduce and make more groups? How does selection play out at this level?

Darwinian selection can play out in a variety of ways. There is differential reproduction of groups, and differential extinction of groups, it can play out through direct competition, and even by differential expansion. However, it’s important to note that adaptive cultural evolution doesn't need to be exactly the same as adaptive genetic evolution. It's not perfectly analogous to Darwinian natural selection. In genetic evolution individuals with a gene need to die out or be out-reproduced. But individual humans do not need to die for culture to evolve, instead we just learn better methods and discard the old ones. We do this throughout the lifespan. The same is true for group-level culture. We copy the culture of other groups, often other successful groups.

Different groups copying each other's culture sounds a bit like horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. What's an example from human culture?

Yes it is like that. Horizontal transfer of cultural elements between groups.

History is littered with groups copying each other. There's a great example from Papua New Guinea of tribe deciding to take on the strategies of the neighboring villages and start farming pigs. Another example is how Japan copied a lot of Western institutions, including universities. Groups of lobster fishermen in Maine copy each other. Sports teams copy strategies. Businesses copy business models. The copying of group culture is everywhere. Another mechanism of group level cultural evolution that is largely distinct from genetic evolution is migration.

What about migration?

If you have a failed state, or if you have a company which is doing poorly, you may have a lot of people leave those groups and go to other ones. And when they do, they do two things. Number one, they adopt the norms and requirements and language and everything else of the group they come into, they become a part of it. And number two, they bring their brainpower with them. This literally shrinks the size and computational ability of one group and adds to the other.

If you're right about a transition in individuality, what kind of future are we moving towards? Are we actually on the way towards being the Borg from Star Trek — a hive mind? Or are there other ways of being eusocial or being a "superorganism" that aren't quite so... scary?

That's a fair question. There are a number of ways in which pop culture has anticipated this kind of science because people see the patterns that we are trying to study. But there are various challenges with these kinds of sort of science fiction ideas that make them hard to map into the science. We don't know what the human future looks like. My interest and the whole point of this research project is to pull people away from the conversations that go too quickly to the future and to focus on the mechanisms — to try to gain some empirical leverage, and to really be careful about how the theory works, to make sure that we can measure things.

But still: there really is a kind of horror associated with losing oneself. It's not sci-fi, but just think about new moms mourning the loss of their individual identity when everyone starts to treat them as "baby's mom" instead of as individuals. Does your work have anything to say about whether we should fear becoming cogs in some great machine?

Look: we are already replaceable cogs in some great machine. When I die, someone else will get my job at the University of Maine and they'll teach some of the same courses. The same is true for everything. It takes only 40 years to make an adult human at the height of their professional capacity. But it takes hundreds of years to make a society schools, hospitals, farms, roads, a justice system, and so on. Over half of humanity now lives in cities. So, to what extent are we already within these great cultural machines? Quite a lot.

So, sure. It's disturbing to think about becoming the Borg. Who knows what the future will look like. But this is the long-term we're talking about — a very long process that's played out over 3 million years so far, with possibly millions of years more to go. So, I think it's very likely that humans of 50,000 to 100,000 years ago would be deeply disturbed and uneasy to be put in a modern city or classroom or grocery store. There are all these strangers around, and we have to take their intentions at face value. So our baseline expectations have shifted. Thankfully, you and I will not have to live in some future society where we are the Borg. It’s not clear that’s where we are going, but if it is, it will almost certainly be more comfortable to those who live then than we imagine it to be from our perspective now.

To that point about already being "cogs in the machine," I think we often forget how brutal the Darwinian baseline is. In natural selection, individuals exist to reproduce or die. In that scenario, we're still replaceable — just in the context of our lineage rather than our society.

That’s right. Natural selection is brutal, and modern city-dwelling humans are not well constructed to survive in the wild. But we don’t have to be. The science of gene-culture co-evolution gives us insights on this. Genes and culture interact, but it’s more complex and interesting than we first imagined. We are beginning to see that cultural organization and infrastructure can support human survival and reproduction so effectively that genes can start to drift, because we're protecting them.

So cultural evolution kind of frees us from selection on genes?

Yes, precisely. We're intentionally idling natural selection. That's what we are really trying hard to do. We have scientific medicine, food science, and all of these industries in order to not have to die, so we can keep reproducing.

So what does your framework predict about the transition in individuality you argue we're going through now?

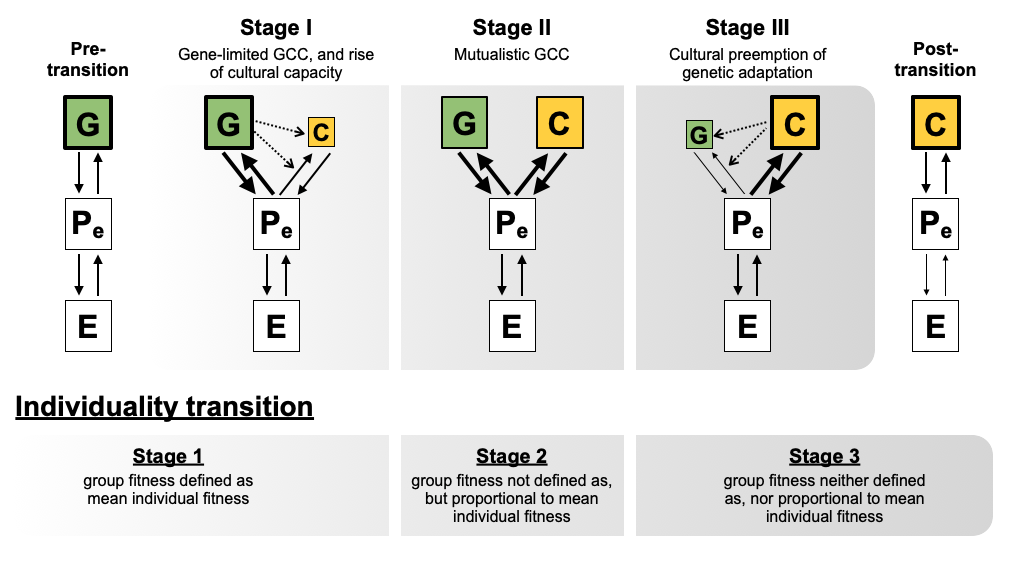

We suggest the transition would likely progress through three stages.

First, we have the emergence of the human ability to learn and transmit culture. How do we start being able to copy other individuals and pass that on? This is the question the literature has mostly been focused. During this phase we evolved the features which are considered universal human traits. These include language, our cooperative nature, and our long adolescent phase, for example. Take our ability to digest things. Humans evolving very streamlined gastrointestinal system because we process and cook food externally. All of these uniquely human traits are the result of gene-culture coevolution.

Then, for some period of time, we think the adaptive strength of genetic and cultural evolution were roughly equivalent. I now suspect this phase was rather brief, in evolutionary terms.

Finally, group-level cultural adaptation overtakes genetic adaptation more decisively.

What stage are we at now?

Zach and I estimate we have recently entered that third and final phase of gene-culture co-evolution. This phase is dominated by a new process of gene-culture co-evolution called cultural preemption in which the cultural strength of the collective brain, if you will, is so strong that human groups can tackle rising challenges with infrastructure and technology and social solutions, and increasingly solve them, sometimes within a generation — thereby avoiding natural selection.

There are a great many examples of this, but they haven't typically been thought of as gene-culture co-evolution because we're usually waiting for genes to change and then we can call that evolution. We realize that’s a mistake. Well, we argue that rapid, group-level cultural adaptation stops genes from undergoing natural selection.

You placed an emphasis on making predictions based on your framework. What are some of those predictions?

There are two major predictions, they're extremely simple. The first is long-term average increases in the importance of cultural information over genetic information for determining phenotypic traits and capacities. The second is long-term average increases in the relative importance of group-level structures for individual survival, health, reproduction, and wellbeing relative to individual-level traits and practices.

What does that look like more explicitly?

A simple way of pointing it out is to ask the question: what matters more for life outcomes like health and wealth, education and happiness, your genes, or the society that you were born into? For a lot of us today, it's very easy to recognize that the society we're born into has a massive impact. Our predictions also include an increased diversification of reproductive strategies. We already discussed the advances in reproductive medicine. The biggest, most obvious one is genetic engineering. It's an evolved cultural process of scientific manipulation of genes to a specification which is culturally determined. We're not doing it for humans at scale yet. But if or when we do, it'd be culture taking the place of genes, just like RNA gave up its place to DNA.

We also predict genetic drift — reduced selection on human genetics. That obviously comes with a big challenge, right? Cultural innovation is allowing us to accumulate what evolutionary biologists call genetic load: negative mutations that we have to be able to manage and deal with as a population. But the way in which we'll do that is not through natural selection, it’s through healthcare.

I think that point about drift and genetic load is worth lingering on for a second. We've been cooking food for a while. Are there any cultural adaptations to genetic load that we're seeing happen today?

One of the best examples of this is the increased likelihood that the daughter of a woman who gives birth by cesarean section will also need cesarean section. That's not surprising, but it's an important example of the fact that we naturally become dependent on things that change the patterns of natural selection. Remember, we are already dependent on the knowledge of others to survive in new environments. We are already dependent on fire. That list is expected to grow.

I think this is where I need to ask a nasty question: Don't you worry that people will pick up this idea that we're allowing deleterious mutations to accumulate in the population and use it to argue for eugenics?

Yes, absolutely. We want to avoid that. My experience so far, however, is that there are biological essentialists who think that people are determined by their genes. These are the people who argue that we need eugenics to improve the gene pool. The error of this perspective is that genes matter less and less all the time.

I have had people across the political spectrum reaching out and wanting to have conversations that I think are unsavory because they believe that our work justifies their political beliefs. It's important to be careful: studying human evolution is not the same as prescribing types of change. It is also not the same thing as saying that one society is more advanced or developed or evolved than another society and should therefore dominate or win or something.

Right. Personally, I think one could take your work and argue not for eugenics but rather for a universal human right to access the cultural technologies we all increasingly rely on. What do you think are the political implications of your work that are actually worth taking seriously?

It does mean a set of things for how we understand political and social change. And I do think it's on me as a scientist, if I think my science is useful, to help make that connection to ethical applications. And the implications I think this work suggests are not traditionally left or right. Folks on the political right sometime believe that humans are bound by a very basic biological blueprint — in a kind of biological determinism that can lead to racist and sexist thinking. So this is wrong. We are a dual-inheritance species. And the evidence suggests that our biology matters less and less.

There are some free market capitalist ideas that competition between economic entities benefits societies. When carefully managed, economic competition can be a strong source of cumulative cultural evolution, and wealth. However, isn't the case that you can have competition at all levels and have a functional society with a military, with health care and with police and an education system. You need to have organized cooperation to build a functional complex society; competition at all levels and between all organizations will break down those group level structures. That is just a fundamental rule of multi-level selection and evolution.

Meanwhile on the left, there's often an assumption that biology doesn't matter and that culture is just what we decide it is. This is also wrong. Biology absolutely matters. It very much has shaped who we are and it provides very major challenges that the left systematically misidentifies. Two of them are racism and sexism. These are both major problems for society because they create inequality and stop people from contributing as they best can. However, the biases that underlie racism and sexism are probably deeply genetically encoded. Not that race is genetically encoded. Instead, there's a lot of evidence to suggest that our ability to pay attention to groups is baked into our genes. The other lesson is that culture is not just what you decide it to be. Culture evolves by its own terms. It's not sort of directly under control as we like to imagine. We can nudge it and influence it, but it's fundamentally a system that's out of our control.

Let's wrap this up by looking ahead. You've put forward this framework now, which makes several predictions about human evolution. What needs to happen to put the science of human cultural evolution on solid footing?

My wish is to take this discussion that's happened in a little corner of evolutionary biology, social science, and philosophy of biology and turn it into real science. That means two things. First, we need to get our theory straight. This paper does that. But we need more than just verbal theory. We need models — mathematical and simulation models to ensure that our theory is logically and internally consistent, and to refine these predictions. Then we need data to test the model predictions. We need to analyze historical and prehistorical patterns. We need to look at current patterns of economic and social change and we need to make predictions for the future. In the ideal world, you'd test models against information on traits and outcomes both of individuals within groups and the traits and outcomes of groups themselves across an entire population of groups over time. It's a giant data collection problem. So we'll try to slice off different pieces as we go.

And I'm putting together a research network of people working on different components of this to share the science more widely. Today, the feeling of out-of-controlness is less of a hard sell than it was 20 years ago. But group-cultural change is not just what's happening in the world today, what we get through the news. It's a pattern of human evolution that goes back very deep. And when you stop and look around, it's amazing when you can see it.

Let's leave it there. Thank you so much for your time!

Thanks for reading

There are many ways you can help:

- Subscribe, if you haven't already!

- Share this post on Bluesky, Twitter/X, LinkedIn, Facebook, or wherever else you hang out online.

- Become a patron for the price of 1 cappuccino per month

- Drop a few bucks in my tip jar

- Send recommendations for research to feature in my monthly paper roundups to elise@reviewertoo.com with the subject line "Paper Roundup Recommendation"

- Tell me about your research for a Q&A post (email enquiries to elise@reviewertoo.com)

- Follow me on Bluesky

- Spread the word!