There's no gene for being human

Barbara Molz found supposedly extinct ancient gene variants in hundreds of modern humans. They don't seem to do much.

What makes us human?

Personally, I think the answer is language.[1] Maybe you think it's being logical. Maybe you're Spock from Star Trek and think it's being illogical. But whatever ultimately makes our species special, it's reasonable to think that the difference that made all the difference must be recorded somewhere, somehow in our genome.

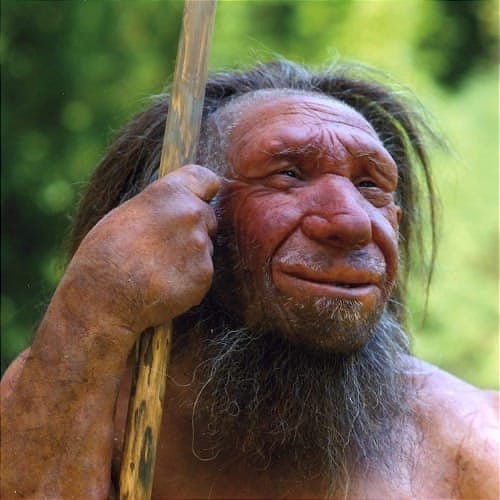

When scientists first got their hands on complete Neanderthal genomes about a decade ago, they identified several genes that appeared to have received a human-specific "update" sometime after our lineage split ways from that of our Neanderthal cousins. All living humans had the new version, Neanderthals had the old version. This was exciting. Might a one of those gene variants have unlocked human cognition? Scientists seriously wondered if there might be a single gene that could explain what makes us human.

Later, as we sequenced more and more human genomes, it turned out that some of those supposedly universal human gene changes aren't actually so universal. While rare, some people do carry the old versions. And they're definitely human.

So what's going on with those ancient variants? Did they actually play a deciding role in human evolution?

Finding out is hard because so few people carry these genes. But thanks to huge datasets like the UK Biobank with its half a million participants, scientists can now catch even vanishingly rare variants. In a study published yesterday in Science Advances, neuroscientist Barbara Molz at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics and her colleagues used UK Biobank data to identify about 100 living people with the archaic versions of supposedly human-specific gene variants. Because the UK Biobank provides both genetic information and data ranging from health metrics and brain scans to whether or not someone likes certain foods, owns a car, or got a university degree, Barbara and her team could look at whether carrying an ancient variant actually had any impact on the lives of real people in the real world.

There was reason to think that missing particular human-specific genetic "updates" might cause trouble. Some of the old variants fall within protein-coding regions of genes. And in a 2022 paper in Science, researchers linked the human-specific version of one gene, TKTL1, to enhanced brain development in animal studies and brain organoids — 3D lumps of neural tissue grown from human stem cells. Might human-specific gene changes have launched us to cognitive heights never reached by our Neanderthal cousins?

Perhaps surprisingly, Barbara's data suggests the answer is no — at least for the gene variants she and her team looked at, the ancient versions didn't seem to have any strong effect in the real world, in real people. This was surprising in the case of TKTL1, especially since the lab results were so suggestive and because this gene is on the X chromosome; men with the archaic variant would have no "backup" copy to lean on, so if there was any strong effect it'd be expected to be obvious in men.

For more on the wonderful weirdness of having two X chromosomes

The archaic version of another gene, SSH2, likewise didn't seem to do much of anything. There were enough carriers among the 500,000 biobank participants that Barbara's team could compare carriers and non-carries from the same ancestry to each other, and their analysis should have picked up a strong effect if there was one. It's still possible that human-specific gene variants contributed to the cognitive revolution that made our species so unique. But no single variant seems to be the key player — the human story is more subtle than that.

I spoke with Barbara about archaic gene variants, biobanking, and what single genes can tell us about what makes us the weird and wonderful talking apes that we are. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you become interested in evolution of language and cognition?

I swapped fields quite a lot — from biology to molecular biology and finally to cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging — but neuroscience was always somehow the linking part. When I joined Simon Fisher's group, I wanted to combine my molecular past with the neuroimaging, so neuroimaging genomics seemed a perfect fit. And, while working on quite a variety of projects, some were in the evolutionary field.

I think the connection between evolution and molecular biology is easy to see — DNA changes, right? But what about neuroimaging?

Mostly what I did in general, but also in the evolutionary domain was to look at how changes in your DNA — variants — influenced differences in brain anatomy and how this can be linked to human evolution. So one project, for example, we looked at the shape of the brain and how DNA variants might have influenced our rounder brain compared to the more elongated version of our Neanderthal cousins.

So the focus is on how genetic changes unlocked human cognition?

In a very broad sense, yes. We look at genetic changes and see if they can help us understand more about the origins of modern humans. And because I am working at a Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, we obviously also have the link to language on our mind. Because the most prominent feature that we gained in our lineage, as modern humans, was indeed our capacity for language. So in the end, we always hope that our research can reveal something about our ability to speak.

How do scientists even identify gene changes that contributed to human evolution?

What we can do now is use comparative genomic approaches. We have access to three quite good quality Neanderthal genomes. This means we can compare modern genomes to those of our extinct Neanderthal cousins, and then kind of assemble catalogues of changes that are unique to our branch — that led to us. Of special interest are "fixed changes," those changes that spread to all humans to become — supposedly — completely fixed on our lineage. So when you look outside, every single human that you find would have one kind of variant, and if you were to go to a Neanderthal, it would have a different variant.

What's so interesting about these fixed variants?

First of all, the ones that have gained most attention in research so far are those that affect protein coding — they are missense changes, changes that substitute one amino acid for another in the protein. So they're supposed to actually do something. And also, these changes show up more in genes that are relevant for human-specific traits, involved in cortical development, for example, and neurogenesis. The field kind of hailed these changes as the entry point for understanding the human condition. They were always super intriguing. Because: why do we have all these changes? People reasoned that they must have been important for something. It was really the thought, looking into these, that they could be the key to understanding what makes us human.

What makes us human — that's a lot to pin on some gene changes. How do scientists know anything about what these archaic variants even do?

Normally, to understand the actual real-life consequences of these changes, you would introduce the human version into animal models or one would use human organoids and reintroduce the archaic, ancestral DNA variants to study the effects.

But now with these huge datasets like UK Biobank, we have this amazing opportunity to really look for present-day, living people who still carry the archaic version of these genes. And UK biobank have collected phenotypic [trait] data — so you can actually try to understand the effects of these changes on health and evolution if there really is something important there. For us, it was really intriguing to actually not go to a model organism but to really dig into the data of present day living people.

Weren't these variants supposed to be universal to all humans?

By the time we started this study, it was already known that there are some individuals who carry the archaic versions, for different reasons. For example, you can always have a back-mutation — something spontaneously happens. But we were not sure how large that sample is. So we were thinking: we now finally have a database that has half a million people. Let's have a look and see how many are actually there.

My last Q&A guest would likely argue that our culture is what makes us human

So that was the core of this study: using a truly huge database to try see how common archaic variants are and check if they have any links to traits we care about, like health?

We already had quite a clear idea which genes to target. Several catalogues of these supposedly fixed changes were published when the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced. And the more human genome sequencing studies came out, the more that list of fixed changes went down, went down, went down. Because obviously you realize, they are not that unique. By 2019, the catalogue our study was focusing on only contained 42 protein-altering changes for which the ancestral version had never been observed in present day living humans. What we wanted to do was, for the first time, really do a thorough search and take a look using a huge dataset. That list was a good place to start, so we thought: let's look at these 42 variants and see how many present-day living people carrying the archaic version that we could find. And we found a lot!

How many is a lot?

It's in the hundreds. Of course they are still super rare — it's not that you have half of people carrying these. They're super rare, but we had 103 carriers that actually had an archaic variant in one of the genes we identified. It's not a massive abundance, but these genes are not completely fixed and totally unique to humans. There are still a few genes where we could not identify a single carrier. So there are still some out there. But I would assume, if you go to even bigger databases, they might also go down. By now I think there is not a single fully, truly fixed position anymore anymore for these protein-coding human-specific differences — or maybe there are just two or three out of the initial list of more than 100 from when the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced.

Was finding a few hundred modern people who carry these ancient gene variants — versions of genes that were previously thought to have changed in all humans — surprising to you?

I have to admit, I was not that surprised! We already expected that somehow that this must be the case. The field had been slowly shifting at the time we did this study [2022–2024]. And we thought that we would definitely identify a few carriers — maybe not for all investigated positions, though. So I was not too surprised.

The ancestry difference was more intriguing — despite the fact that UK Biobank is heavily biased towards white Europeans, we still found a lot of carriers from other ancestries.

Looking at the study, about half of the 103 people with archaic variants were from non-European ancestries despite those groups making up just around 5% of the sample. Is that maybe a hint that genomics research has at least partially overlooked important aspects of human diversity?

The thing is, genetic and genomic studies in general were predominantly based on populations of European ancestry. The field didn't study everyone else well. And this kind of already implies that everything was built on only a small subset of all of the diversity out there. So I think there should be a big global effort towards genomic equity in general.

While it is known that some isolated populations have higher levels of archaic ancestry just because of their evolutionary history, for instance the Khoe-San.[2] This could be some of the explanation why we get more hits for ancestral variant. The finding was still intriguing and shows that looking at just one part of the puzzle will not give us whole insights. In other ancestries, we have not found any hits for ancestral genes at all —we simply didn't know what we'd find, as there’s not good enough references out there for other ancestries.

What traits were you interested in specifically?

In UK Biobank, there's a massive abundance of phenotypes. We have about 5000 different brain imaging phenotypes from, by now, nearly 100,000 participants. When I did the study it was about 40,000. But then you also have health questionnaires, you have information about qualification, status, vision, hearing measures, but also information on your eating preferences for example. It's a full array that covers tons of domains, from socioeconomic status to health records to brain imaging, the heart, bloodwork, etc. In the end, we pre-selected just a few traits we had prior reasons to think would be relevant.

It's really interesting that when you say phenotype, you're not just talking about how our bodies look and work but also things like whether or not you got a college degree.

Yeah, exactly. Socioeconomic factors like what job status,, education, what type of house you have, whether you have cars, are included. While factors like IQ are not always the best and heavily linked to socioeconomic factors, our paper used qualification level as a kind of a rough proxy for cognitive capacities.

In your study, you ended up focusing on two specific genes and looking at whether or not they really do contribute to cognition in living humans. Let's start with SSH2. What is it and why did you narrow in on it?

SSH2 is a bit of a two-faced thing. On the one side, we were interested in it because the encoded protein is thought to potentially affect key cellular processes. So we would hope to see some effects. But on the other hand, there were more pragmatic reasons to look at it: we found 19 carriers in a very specific ancestry cluster. That's practical, because if you have a lot of diverse ancestries, any kind of analysis is much more complicated. But here, we had 19 carriers from the same ancestral background, and so with that sample size we should have had enough power to detect moderate to strong effects.

And what did you find when you looked at the phenotypic data of people with the archaic version of SSH2?

The takeaway is that we found nothing. We found no difference. Obviously, there was no formal statistical analysis here. There were too few people. But since the effect of this fixed variants was supposed to be large, we hypothesized that anything dramatic should be clearly visible. And in all of the things that we looked at like qualifications status, body size, general health, smoking vs nonsmoking, and lots of neuropsychological traits — we found no obvious divergence from the norm. So it looks like there is at least no strong effect that we can detect. It might be that there are moderate or more subtle differences. But to find those, we'd need larger sample sizes to really be sure and do a proper statistical analysis.

So this gene does not look like it "made us human," at least not on its own.

Definitely not, no. But I think for SSH2, this was still a nice way to show how you can use biobanks. We tried to be as thorough as possible by pre-selecting traits, having a proper, thorough hypothesis why these traits were chosen because they'd already been linked to the traits we chose in prior studies looking at Neanderthal admixture.

What about the other gene, TKTL1? This one had previously been linked to big effects on brain development, right?

For TKTL1, it was a bit of a different story. It was already known that the human-specific variant of this wasn't entirely fixed. But a previous study using animal models and gene-edited organoids suggest there was a specific effect of this variant. It showed greater neurogenesis in the frontal neocortex with the human version of TKTL1 compared to the ancestral, Neanderthal version.

Based on those findings we really expected some effects in the frontal lobe of the brain, for example, or more generally, on cognition.

So, because we have phenotypic data for people in UK Biobank, and because we knew the frontal lobe might be affected and there was a significant effect reported already, we had a more targeted approached compared to SSH2. And because this variant is on the X chromosome, males with just one X and one Y therefore only carry either the archaic version or the modern human version — any effect that you would expect should be super prominent in males. Here, we very clearly expected to actually see something.

That's why I selected participants that also had brain imaging data available and had a specific look at the frontal lobe. And because this variant had also been linked to cognition, we had a look at whether these people — very simplistically — went to university or not and what degrees they had. If the change in the gene really affects cognition in a big way, you would not necessarily expect someone carrying the archaic variant to have a higher university degree.

And did you find anything?

No, people with the archaic version of TKTL1 didn't show any very obvious differences again — in their brains or in their qualification levels.

What should these two null results tell us about the evolution of human cognition?

First of all, what you can see from the TKTL1 story is that results from laboratory settings sometimes indicate very dramatic effects, but you can't necessarily translate those lab-based experiments to real-world impacts on living human beings. Lab studies are super valuable, but it's not like if a lab study shows a super significant effect of a gene that it means that people who carry it can't go to university — that's one thing we show.

Also, we highlighted that there's an ever-decreasing number of completely fixed sites. And I think the field should start to abandon the notion that something is fully fixed and broaden the scope a bit. So I think that's a big message: Hey, don't focus just on these. Have a look at higher-frequency variants, too, because there are a lot more and the more you have, the bigger your sample sizes get and the better statistical approaches you can use.

And personally, I think if you look at one single human-specific change alone, that it might not be so informative. I think you should really focus on the aggregated effects of multiple differences.

Genetic changes don't have to guarantee any particular outcome of development. Often, it's better to think of them as simply changing the odds of one trait or another.

You mentioned earlier that you think we should push for more diverse data in biobanking, too. Does that mean just people of diverse ancestries or is there a kind of data — a trait, maybe — that you feel is missing, too?

Something we came across is that many biobanks lack information on traits that are particularly relevant for evolution. Especially language. UK Biobank, for instance, lacks language measures. And that's the thing I was looking at with the study of SSH2: what trait would you pick to define the human condition? It's super hard to pick a single thing. The most prominent one that I would think of is that we can speak, but there are no, or just very limited measures of people’s skills in this domain. So I think biobanking efforts should also focus more on language.

Has your work changed how you think about the human story at all? About what makes us human?

The notion of single genes somehow unlocking human cognition has not been relevant for a while now. These days, we don't see the Neanderthals as our lower cousins, you know. They were probably not that far away from us in their behavior, there's not a huge difference. I think the field has, for a while, already been changing— it seems unlikely that one single change in a gene suddenly made us different. I think many tiny changes had to come together for this. And also, not all human-specific changes are beneficial. Some might have been neutral and others might have deleterious side effects or increased our risks for neurodevelopmental disorders. So more and more, it seems that there were likely many changes with each having a subtle and a lot more fine-grained effect and we likely need to develop methods that can better tease apart how multiple evolutionary changes interact to shape human biology.

And while we used biobanks for this study, I think all sides are important. We can use biobanks to study real-life effects. But on the other side, the lab-based work can look at it in a more fine-grained way and see how these variants really, underneath, change something on a mechanistic level. You need as much information as you can get from different angles to really figure out what made us human.

Perfect, let's leave it there. Thank you!

Footnotes

[1]: I unironically believe that the emergence of human language deserves to stand alongside the emergence of life as one of the great unsolved mysteries of science.

[2]: The Khoe-San are descendants of an early migration of modern humans to southern Africa some 150,000 years ago

Thanks for reading

There are many ways you can help:

- Subscribe, if you haven't already!

- Share this post on Bluesky, Twitter/X, LinkedIn, Facebook, or wherever else you hang out online.

- Become a patron for the price of 1 cappuccino per month

- Drop a few bucks in my tip jar

- Send recommendations for research to feature in my monthly paper roundups to elise@reviewertoo.com with the subject line "Paper Roundup Recommendation"

- Tell me about your research for a Q&A post (email enquiries to elise@reviewertoo.com)

- Follow me on Bluesky

- Spread the word!