The origin of life wasn't fat-free

James Sáenz studies how fatty molecules might have helped life get started

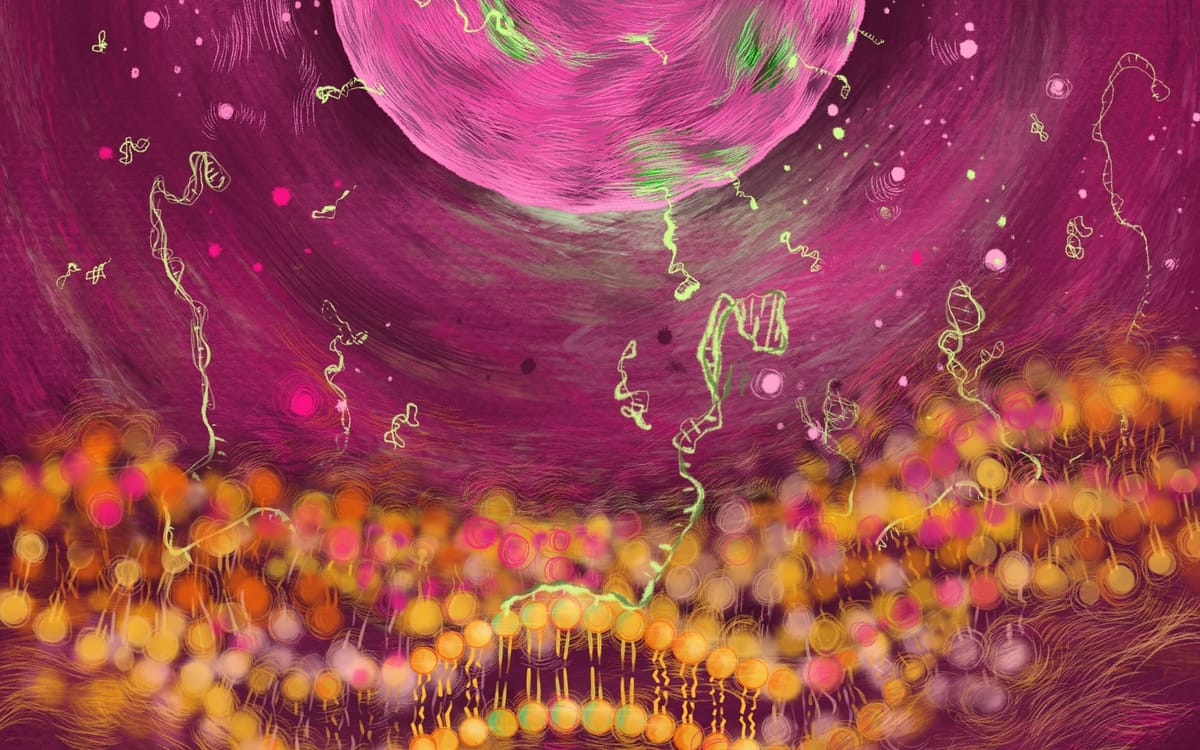

Lipids are not exactly the star of the origin of life show.

Despite quite literally holding every single cell on Earth together, these fatty molecules (think oils, fats, waxes, etc.) are basically an afterthought in most origin of life hypotheses. If lipids appear in biological origin stories all, it is usually only to provide a vessel that contains and concentrates the real protagonists of prebiotic chemistry: proteins and nucleic acids. Origins research is, broadly, divided into two camps. The information-first camp that generally sees the origin of life as the emergence of a self-replicating RNA molecule is understandably more interested in RNA than fats. In the other camp, metabolism-first thinking that sees life as a self-sustaining chemical network and usually places its origin at deep-sea hydrothermal vents, lipids were a bit of a problem for a while — scientists had trouble getting lipid vesicles to form in hot salty water. They eventually solved that problem. And besides, there's a solution to prebiotic dilution that doesn't involved lipids at all; pores in the rock around hydrothermal vents might have filled in for cell membranes at the origin of life.

If you think I am exaggerating how much of a non-issue lipids are in the origins field, I would refer you to this quote from a recent paper reporting the discovery of sugars in material returned from the asteroid Bennu:

Given that the fragments of carbonaceous asteroids appear to be widely distributed in the inner solar system, such asteroids or fragments of asteroids (for example, carbonaceous chondrites), would have provided glucose and other bio-essential sugars to broad areas of the inner solar system, together with nucleobases and protein-building amino acids. Thus, all three crucial building blocks of life would have reached the prebiotic Earth and other potentially habitable planets. (Emphasis mine)

Sugars, nucleobases, and amino acids — the simple molecules that chain together in carbohydrates, nucleic acids like RNA and DNA, and proteins — are all three ingredients needed for life, apparently.

To be charitable about the three-ingredient recipe for life, it isn't even wrong — so long as you think an isolated self-replicating RNA counts as life, which plenty of scientists do. Hell, I was recently at a whole workshop full of artificial life researchers who were wishy-washy on whether or not self-replicating, evolving snippets of code might be considered alive or not (many called their code snippets "creatures," which I found very cute). Granting creature-hood to self-replicating RNAs, maybe the amino acids in Bennu are even a bit superfluous. With sugar and nucleobases, you'd have all two ingredients necessary for life. But you're obviously not getting from that self-replicating RNA to an actual cell without lipids. There's no cutting the fat from origins.

That's why, basically the day I read that Bennu sugars paper, I shot off an email to James Sáenz. James is a geochemist-turned-synthetic biologist at the Dresden University of Technology who studies lipids — including the role these molecules might have played in the origin of life.

Like basically every interdisciplinary scientist I talk to, James' brain seemed to have had a little short-circuit when I asked him what kind of scientist he is. And like basically every origins scientist I talk to, he was drawn into science by the Big Questions, not by a desire to work in a specific field. As a kid, James was fascinated by evolution. But he chose to study geology in college instead of biology because he didn't think he could keep up with the pre-meds (it was a bit of a "rocks for jocks" situation, he told me). Recalling that Darwin had been a geologist and a close friend of geology pioneer Charles Lyell, James realized Earth science offered its own way to read life's story. And in graduate school, he started working with lipids for the first time; fatty molecules can stick around for eons in sediments, and organic geochemists can analyze their molecular "fossils" to determmine what organisms lived long ago. This is how researchers are figuring out what ancient ecosystems looked like during dramatic deep-freeze Snowball Earth periods, for instance. After graduate school, James was able to take what he'd learned about lipids by studying ancient molecular fossils to study what these molecules do in modern organisms — and how they might have contributed to the origin of life.

James and his colleagues are showing that lipids do far more than just encapsulate more interesting chemistry. They're not just a stage. They're players. And before the first cells, they might have played entirely different roles than they do in modern cells. It's even possible that lipids controlled the activity of RNA enzymes or ribozymes, like a kind of primitive biochemical switch for the RNA world.

I spoke with James about why lipids are so often overlooked in origins of life research and about two fascinating projects that hint at the roles of lipids in early life: one on lipids as switches for ribozymes, and another on the tiniest possible set of lipids needed for life (just two are enough). This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This is not a paywall!

Subscribe for free to keep reading.