There is no time telescope

The Mars that may have hosted life long ago is our neighbor in space only.

The 90s are back: flannel shirts, heroin chic, and NASA scientists getting on TV to talk about signs of life in ancient Mars rocks.

On August 7 1996, NASA held a press conference to tell the world that its scientists had probably found evidence for ancient life in a Mars rock. Allan Hills 84001, a potato-sized chunk of 4 billion-year-old Martian stone, had fallen over Antarctica during the last Ice Age as a meteorite after being blasted away from its home planet in an impact event and drifting through space for several million years. Not only was ALH84001 from Mars and one of the oldest rocks ever discovered, it also contained globules of carbonate minerals that suggested a brush with liquid water — and which, on Earth, can form with help from life. Electron microscopy of the carbonates revealed nanoscale structures that recall Earth microbes. Together with organic material and unusual magnetic crystals similar to those made by a handful of terrestrial lifeforms, those "microfossils" were enough evidence to convince a team of NASA researchers that they might have found fossil aliens. Then-President Bill Clinton even met the press on the White House lawn to comment on the groundbreaking discovery.

Now, just about 29 years later, scientists are getting excited about a new Mars rock. This one, unlike ALH84001, is still on Mars — a strip of 3.5 billion-year-old mottled red stone called Cheyava Falls in the Bright Angel formation, which sits on the floor of a river-carved canyon upstream of a lake that was dry when Earth's first continents first rose above the primordial ocean. On September 10, NASA held a press conference to announce that the Perseverance Rover had found unusual mineral speckles in Cheyava Falls that could be the leftovers of ancient microbial activity.

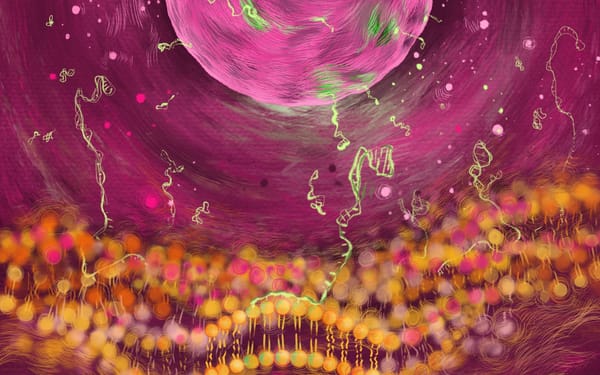

The exciting features are nodules of carbonate minerals enriched in iron and sulfur, dubbed "leopard spots" and "poppy seeds." To get just a bit more technical, the iron and sulfur minerals in these nodules are reduced, meaning they've had electrons dumped on them. Plenty of Earth microbes that don't breathe oxygen get their energy by shunting electrons from the organic carbon onto iron and sulfur, which they "breathe." Some iron-breathing microbes also produce carbonate blobs. And there's organic material — probably messy ringed molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which form basically everywhere in space — in the rock, too. So the mineral nodules could conceivably be fossil microbe waste.

The agency's interim administrator Sean Duffy — an unqualified Trump appointee and former competitive lumberjack who looks like an AI-generated average of every dude who's ever appeared in a shaving cream commercial — hailed it as "the closest we have ever come to discovering life on Mars."[1]

Though I hadn't even been born in 1996, I can't help but feel a bit of déjà vu. As one of the scientists who peer-reviewed the new results pointed out, Cheyava Falls sounds quite a lot like ALH84001. Both rocks contain similar organic molecules, reduced iron and sulfur, and carbonate nodules. All that's missing are the unusual magnetic crystals and tiny "dubiofossils" — though they could be there, too. Perseverance wouldn't be able to tell.

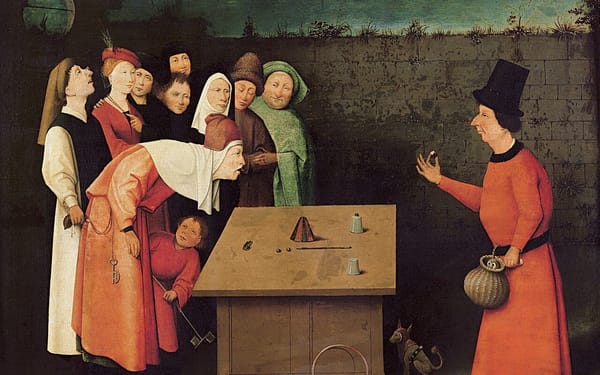

ALH84001, of course, is famous three decades after Bill Clinton's unusual announcement not because it settled the question of life on Mars, but because it did not. After much controversy and follow-up work, astrobiologists have mostly dismissed the ALH84001 biosignature as a false alarm. When I learned about ALH84001 as a geobiology undergrad in the late 2010s, it was taught as a kind of cautionary tale: don't be the scientist who cried alien.

There is no time telescope. There are only old rocks.

Perhaps this is why I struggled to get excited about the Cheyava Falls biosignature claim. Eventually, though, I started to worry I'd missed out on something big and texted an astrobiologist friend to ask how hyped I should be about this thing. He sent me a link to a news story he'd been quoted in. The verdict? This was exciting, but by no means conclusive evidence of life — to settle the score, we'd need to bring the rock back to Earth. When I finally pulled up the paper to take a look for myself, my inner dialogue was far more cynical. Odd minerals in a very old rock. Oh, great. Here we go again.

Practically every discussion of the Cheyava Falls biosignature I've encountered — from the paper itself to the press release and the many news articles and videos it inspired — ends with a similar refrain: to actually know if this rock is evidence of life, we'll need to get a sample back to Earth for analysis.[2]

Distance, in other words, is the problem. Mars is far away, accessible only to robotic explorers that, while sophisticated, can't hold a candle to a human scientist with a fancy lab. If only we could analyze this thing in an Earth lab, the thinking goes, we'd know for sure.

But is that even true?