Paper Roundup September 2025: Mars life, exploding black holes, quantum computing

Papers tackling the biggest questions in science, curated by hand each month.

Every month, I publish a curated list of the most fascinating, groundbreaking inflammatory, or otherwise bold new scholarship on the "big questions" of science. Inclusion is not endorsement. Think something should be included in next month's paper roundup? Shoot me an email at elise@reviewertoo.com.

If you liked this newsletter, why not share it with a friend or post it on Bluesky or wherever else you hang out online? That's the best way to help this project continue!

Don't miss next month's newsletter!

Highlights

Best evidence yet for ancient life on Mars

Redox-driven mineral and organic associations in Jezero Crater, Mars (Nature, September 10) by Joel A. Hurowitz, M. M. Tice, A. C. Allwood, M. L. Cable, K. P. Hand, A. E. Murphy, K. Uckert, J. F. Bell III, T. Bosak, A. P. Broz, E. Clavé, A. Cousin, S. Davidoff, E. Dehouck, K. A. Farley, S. Gupta, S.-E. Hamran, K. Hickman-Lewis, J. R. Johnson, A. J. Jones, M. W. M. Jones, P. S. Jørgensen, L. C. Kah, H. Kalucha, T. V. Kizovski, D. A. Klevang, Y. Liu, F. M. McCubbin, E. L. Moreland, G. Paar, D. A. Paige, A. C. Pascuzzo, M. S. Rice, M. E. Schmidt, K. L. Siebach, S. Siljeström, J. I. Simon, K. M. Stack, A. Steele, N. J. Tosca, A. H. Treiman, S. J. VanBommel, L. A. Wade, B. P. Weiss, R. C. Wiens, K. H. Williford, R. Barnes, P. A. Barr, A. Bechtold, P. Beck, K. Benzerara, S. Bernard, O. Beyssac, R. Bhartia, A. J. Brown, G. Caravaca, E. L. Cardarelli, E. A. Cloutis, A. G. Fairén, D. T. Flannery, T. Fornaro, T. Fouchet, B. Garczynski, F. Goméz, E. M. Hausrath, C. M. Heirwegh, C. D. K. Herd, J. E. Huggett, J. L. Jørgensen, S. W. Lee, A. Y. Li, J. N. Maki, L. Mandon, N. Mangold, J. A. Manrique, J. Martínez-Frías, J. I. Núñez, L. P. O'Neil, B. J. Orenstein, N. Phelan, C. Quantin-Nataf, P. Russell, M. D. Schulte, E. Scheller, S. Sharma, D. L. Shuster, A. Srivastava, B. V. Wogsland, and Z. U. Wolf

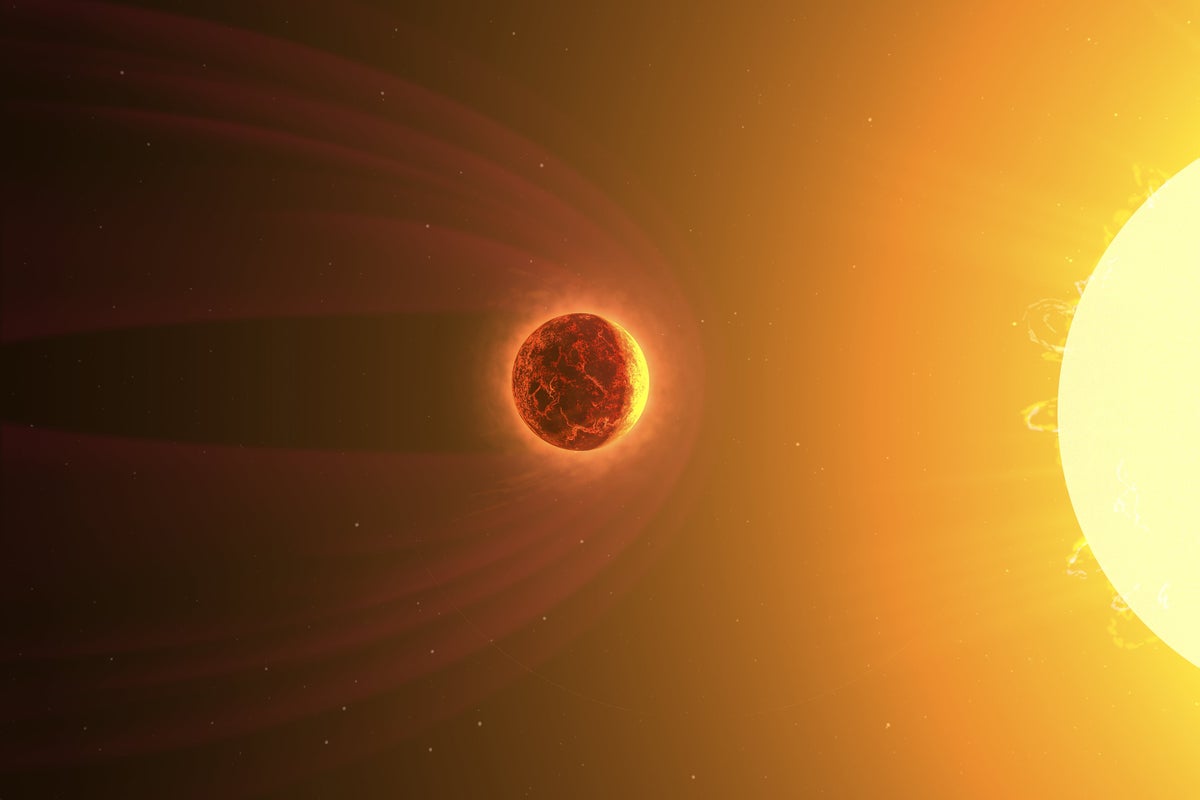

This month brought some of the most exciting astrobiology news in a while: NASA's Perseverance rover spotted mineral globules in a rock near Jezero Crater that might be the metabolic leftovers of ancient microbes. So, of course, I'm going to be a bit of a downer about it. While I think it probably is fair to call this the best evidence yet for life on Mars, that does not make it good evidence. Contrary to media claims, a similar rock would probably not be widely accepted as evidence for ancient life on our own planet — geochemical evidence alone usually doesn't fly in the "earliest evidence of life on Earth" game.

As a former Earth scientist, I can't help but feel that this is another case of space exploration getting so focused on overcoming the challenge of distance in space that they forget about distance in time. We recognize that it's hard to know things about planets because they're far away; one of my favorite little factoids is that we only recently confirmed that there are active volcanoes on Venus, our closest neighbor. And yet we somehow expect to be able to know enough about the surface of Mars 3.5 billion years ago to know if some weird minerals are the kind of weird that only life can explain? Overcoming distance is a technical challenge; with enough money and time, we can build telescopes and spacecraft capable of revealing faraway worlds in great detail. But as I pointed out in last week's post, there is no time telescope. There are only old rocks. And the worlds those old rocks came from are not just far away, but largely lost.

And now for a bit of unsubstantiated speculation: I wouldn't be surprised to learn that that NASA scientists dragged this rock into the spotlight at least partially in a bid to spare Mars Sample Return from the Trump admin's chopping block. Variations on the "we need to get this thing back to an Earth lab to know for sure about aliens" theme echoed throughout the press conference. Who knows, maybe the strategy will work — after all, the shaky claim of biosignatures in Martian meteorite ALH84001 contributed to a boom in NASA Science funding in the late 1990s, despite steep cuts to the rest of the administration.

We're probably about to see a black hole explode

Could We Observe an Exploding Black Hole in the Near Future? (Phys. Rev. Lett., September 10, 2025) by Michael J. Baker, Joaquim Iguaz Juan, Aidan Symons, and Andrea Thamm

Did you know that black holes can explode? I did not. It all sounds quite horrifying and universe-ending, but apparently scientists expect this and it is Fine. Explosions happen because black holes very slowly eat away at their own mass and emit Hawking radiation — when the mass dips down to zero, there's an enormous explosion.

Current gamma ray observatories would be able to spot such an explosion if it happened now. And new calculations suggest that our odds of spotting such an event might be far higher than previously thought — depending on what flavor of beyond-the-standard-model physics you ascribe to, there's up to a 90% chance we'll witness a black hole explosion within the next 10 years.

Observing such an explosion would be very helpful. Black holes evapoprate slowly, so it would only be primordial black holes from the beginning of the universe that we'd see exploding now — seeing one go kaboom would prove that they exist. It'd also provide the first direct measurements of Hawking radiation, and even give scientists information about Nature's repertoire of fundamental particles.

Quantum leap

Continuous operation of a coherent 3,000-qubit system (Nature, September 15) by Neng-Chun Chiu, Elias C. Trapp, Jinen Guo, Mohamed H. Abobeih, Luke M. Stewart, Simon Hollerith, Pavel L. Stroganov, Marcin Kalinowski, Alexandra A. Geim, Simon J. Evered, Sophie H. Li, Xingjian Lyu, Lisa M. Peters, Dolev Bluvstein, Tout T. Wang, Markus Greiner, Vladan Vuletić, and Mikhail D. Lukin

For quantum computers to work, isolating qbits from the environment is key; when quantum entities bump up against the rest of the world, they lose their wonderful weirdness. That's one reason quantum computing researchers are excited about using neutral atoms as qbits. Because they lack charge, they're easier to keep isolated — and, therefore, to keep quantum. But quantum computing systems based on neutral atoms have a persistent flaw. They're leaky. They lose atoms, and therefore can't be run for very long before they stop working. Earlier this month, researchers at Caltech broke the record for the largest and longest-lived qbit array with a grid of 6100 Cesium atoms that could remain in superposition for about 13 seconds — 10 times longer than previous arrays.

Now, a team led by MIT and Harvard researchers has built a grid of 3,000 atomic qbits that can theoretically run forever. It still loses atoms. But the researchers got around that problem by using optical tweezers to constantly replace lost qbits in a way that doesn't disrupt the information stored in the array. In the 2 hours the researchers maintained their qbit grid, it cycled through more than 50 million atoms.

I found this fascinating not just because it seems like a potentially impotant advance in quantum computing, but because the way the computer works reminds me of life: despite constantly replacing its constituent physical parts, it maintains its informational structure. It's in a state that chemist Addy Pross calls dynamic kinetic stability — the stability of water fountains, the mythical Ship of Theseus, and living things. Last author Mikahil Lukin apparently saw the connection, too:

"We can literally reconfigure the atomic quantum computer while it's operating," said Lukin. "Basically, the system becomes a living organism." (Harvard Gazette, September 25 2025)

Book: AI meets evolution

What Is Intelligence? Lessons from AI About Evolution, Computing, and Minds (MIT Press, September 23) by Blaise Agüera y Arcas

Speaking of dynamic kinetic stability, AI researcher and Google VP Blais Agüera y Arcas just published a new open-access book on AI through the lens of evolution and cognition with MIT press. I say "speaking of dynamic kinetic stability" because Agüera y Arcas has done some fascinating work on how snippets of computer code held in a state of dynamic kinetic stability — that is, a state of constant overturn — can evolve from simple to complex. That's a big deal, because most lab experiments with self-replicating molecules just lead to smaller, simpler molecules. It is only in a few cases that scientists have engineered artificial systems on computers or in test tubes that go the other way.

Consciousness adversarial collaboration continues

Integrated information and predictive processing theories of consciousness: An adversarial collaborative review (arXiv preprint, August 30) by Andrew W. Corcoran, Andrew M. Haun, Reinder Dorman, Giulio Tononi, Karl J. Friston, Cyriel M. A. Pennartz, and the TWCF: INTREPID Consortium

If you're looking for a primer on the consciousness wars, look no further. This review, co-written by several of the most prominent researchers in the field, is a kind of roadmap laying out the three main theories being put to the test in an ongoing adversarial collaboration initiative. Those theories are: Integrated Information Theory or IIT, Neurorepresentationalism or NERP, and Active Inference — in this case mostly meaning the Free Energy Principle and related ideas. Section 3 is, I think, the most interesting. It outlines and compares the empirical predictions of each theory and puts forward several hypotheses that might actually be testable.

Adversarial collaboration in consciousness seems to be having something of a moment; earlier this year, an adversarial collaboration of IIT and Global Workspace Theory researchers published their first results in Nature. Time will tell what these collaborations bring, but it's nice to see a tricky field taking its trickiness seriously.

The state of exoplanet astronomy

Characterization of Exoplanets in the James Webb Space Telescope Era (PNAS Special Feature, September 22)

This month, PNAS published a special feature on the current state of exoplanet astronomy: "Characterization of Exoplanets in the James Webb Space Telescope Era." This star-studded collection consists of an introduction by Jonathan Lunine and Neta Bahcall, a research article on the metallicity of a warm giant planet, and four reviews by scientists whose names you'll recognize if you're into exoplanets:

- Exploring exoplanet dynamics with JWST: Tides, rotation, rings, and moons by Sarah Millholland and Joshua Winn

- Prospects for detecting signs of life on exoplanets in the JWST era by Sara Seager, Luis Welbanks, Lucas Ellerbroek, William Bains, and Janusz J. Petkowski

- Exploring the sub-Neptune frontier with JWST by Nikku Madhusudhan, Måns Holmberg, Savvas Constantinou, and Gregory J. Cooke

- A first look at rocky exoplanets with JWST by Laura Kreidberg and Kevin B. Stevenson

Are "eureka" moments phase transitions?

An information-theoretic foreshadowing of mathematicians’ sudden insights (PNAS, August 18, 2025) by Shadab Tabatabaeian, Artemisia O’bi, David Landy, and Tyler Marghetis

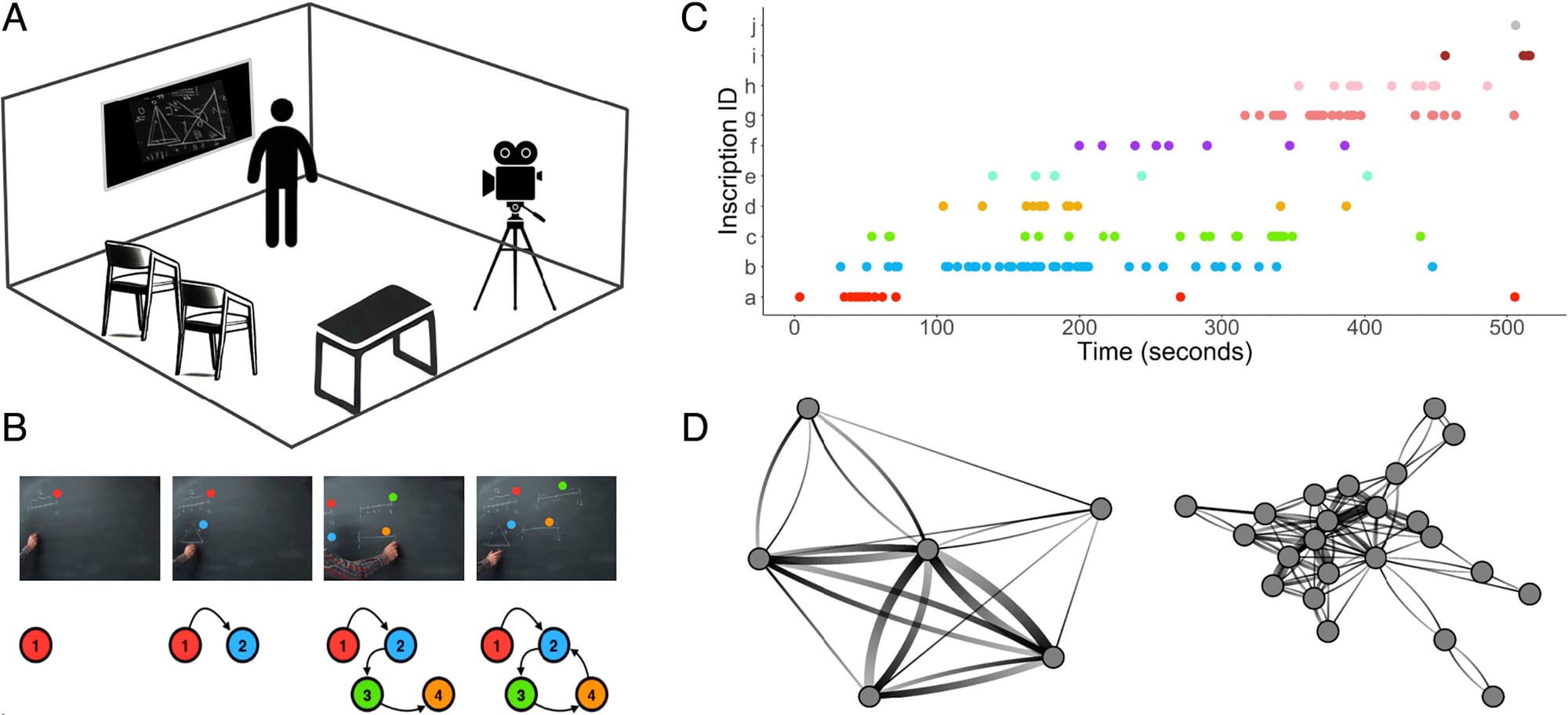

In what has to be the most delightful study I encountered this month, researchers treated mathematical insight as a critical phase transition to try and predict "eureka" moments by looking for the increasingly wild fluctuations expected as a system approaches criticality. The idea is that flashes of insight are not "out of nowhere" any more than ice melting after being heated for a while is "out of nowhere."

For the study, the team made and analyzed video recordings of mathematicians working on proofs at blackboards and tested whether they could predict whether they were about to have a "eureka" moment. These were no little puzzles: the tasks were drawn from the William Lowell Putnam Mathmatical Competition, in which mathematicians have 6 hours to try to solve 12 problems — and the median score is 0 or 1 point out of 120 total. The researchers focused on attention shifts, which they defined as occuring when a mathematician jumped from one "inscription" on the blackboard to another. They also tracked things like muttering to oneself and exclaiming "aha!"

The paper is fun and potentially useful if you buy that the method could be extended to other contexts. But that's not all. It is also delightfully funny and self-aware:

Using naturalistic video recordings of mathematicians working on proofs “in the wild” (i.e., in their own offices and seminar rooms), we show that insights that appear to come out of nowhere are actually prefigured by changes in how mathematicians are writing and gesturing.

👏 Make 👏 papers 👏 fun 👏 again 👏

Don't miss the next paper roundup! Subscribe to R2 to stay on top of the biggest ideas in astrobiology, origins of life, and complexity science.

The Rest

The Universe

- Probing Vector Chirality in the Early Universe (Phys. Rev. Lett., September 30) by Junsup Shim, Ue-Li Pen, Hao-Ran Yu, and Teppei Okumura.

- Cosmic Birefringence from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope Data Release 6 (arXiv preprint, September 17) by P. Diego-Palazuelos and E. Komatsu

- Illuminating Black Hole Shadows with Dark Matter Annihilation (Phys. Rev. Lett., September 16) by Yifan Chen, Ran Ding, Yuxin Liu, Yosuke Mizuno, Jing Shu, Haiyue Yu, and Yanjie Zeng

- The emergence of globular clusters and globular-cluster-like dwarfs (Nature, September 10) by Ethan D. Taylor, Justin I. Read, Matthew D. A. Orkney, Stacy Y. Kim, Andrew Pontzen, Oscar Agertz, Martin P. Rey, Eric P. Andersson, Michelle L. M. Collins, and Robert M. Yates

Planets

- A Cold and Super-Puffy Planet on a Polar Orbit (arXiv preprint, September 30) by Juan I. Espinoza-Retamal, Rafael Brahm, Cristobal Petrovich, Andrés Jordán, Thomas Henning, Trifon Trifonov, Joshua N. Winn, Erika Rea, Maximilian N. Günther, Abdelkrim Agabi, Philippe Bendjoya, Hareesh Bhaskar, François Bouchy, Márcio Catelan, Carolina Charalambous, Vincent Deloupy, George Dransfield, Jan Eberhardt, Néstor Espinoza, Alix V. Freckelton, Tristan Guillot, Melissa J. Hobson, Matías I. Jones, Monika Lendl, Djamel Mekarnia, Diego J. Muñoz, Louise D. Nielsen, Felipe I. Rojas, François-Xavier Schmider, Elyar Sedaghati, Guðmundur Stefánsson, Stephanie Striegel, Olga Suarez, Marcelo Tala Pinto, Mathilde Timmermans, Amaury H. M. J. Triaud, Stéphane Udry, Solène Ulmer-Moll, and Carl Ziegler

- A Thick Volatile Atmosphere on the Ultra-Hot Super-Earth TOI-561 b (arXiv preprint, September 23) by Johanna K. Teske, Nicole L. Wallack, Anjali A. A. Piette, Lisa Dang, Tim Lichtenberg, Mykhaylo Plotnykov, Raymond T. Pierrehumbert, Emma Postolec, Samuel Boucher, Alex McGinty, Bo Peng, Diana Valencia, and Mark Hammond

- Possible Evidence for the Presence of Volatiles on the Warm Super-Earth TOI-270 b (arXiv preprint, September 17) by Louis-Philippe Coulombe, Björn Benneke, Joshua Krissansen-Totton, Alexandrine L’Heureux, Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb, Michael Radica, Pierre-Alexis Roy, Eva-Maria Ahrer, Charles Cadieux, Yamila Miguel, Hilke E. Schlichting, Elisa Delgado-Mena, Christopher Monaghan, Hanna Adamski, Eshan Raul, Ryan Cloutier, Thaddeus D. Komacek, Jake Taylor, Cyril Gapp, Romain Allart, François Bouchy, Bruno L. Canto Martins, Neil J. Cook, René Doyon, Thomas M. Evans-Soma, Pierre Larue, Alejandro Suárez Mascareño, and Joost P. Wardenier

- The Photochemical Plausibility of Warm Exo-Titans Orbiting M-Dwarf Stars (arXiv preprint, September 12) by Sukrit Ranjan, Nicholas F. Wogan, Ana Glidden, Jingyu Wang, Kevin B. Stevenson, Nikole Lewis, Tommi Koskinen, Sara Seager, Hannah R. Wakeford, and Roeland P. van der Marel

- First JWST thermal phase curves of temperate terrestrial exoplanets reveal no thick atmosphere around TRAPPIST-1 b and c (arXiv preprint, September 2) by Michaël Gillon, Elsa Ducrot, Taylor J. Bell, Ziyu Huang, Andrew Lincowski, Xintong Lyu, Alice Maurel, Alexandre Revol, Eric Agol, Emeline Bolmont, Chuanfei Dong, Thomas J. Fauchez, Daniel D.B. Koll, Jérémy Leconte, Victoria S. Meadows, Franck Selsis, Martin Turbet, Benjamin Charnay, Laetita Delre, Brice-Olivier Demory, Aaron Householder, Sebastian Zieba, David Berardo, Achrène Dyrek, Billy Edwards, Julien de Wit, Thomas P. Greene, Renyu Hu, Nicolas Iro, Laura Kreidberg, Pierre-Olivier Lagage, Jacob Lustig-Yaeger, and Aishwarya Iyer

Biosignatures and SETI

- Detection of organic compounds in freshly ejected ice grains from Enceladus’s ocean (Nature Astronomy, October 1) by Nozair Khawaja, Frank Postberg, Thomas R. O’Sullivan, Maryse Napoleoni, Sascha Kempf, Fabian Klenner, Yasuhito Sekine, Maxwell Craddock, Jon Hillier, Jonas Simolka, Lucía Hortal Sánchez, and Ralf Srama

- Insights from early life in the 3.45-Ga Kitty’s Gap Chert for the search for elusive life in the Universe (Nature Astronomy, September 19) by Frances Westall, Graham Purvis, Naoko Sano, Jake Sheriff, Laura Clodoré, Frédéric Foucher, and Tetyana Milojevic

Origins and Artificial Life

- Heat-rechargeable computation in DNA logic circuits and neural networks (Nature, October 1) by Tianqi Song and Lulu Qian

- Life at the boundary of chemical kinetics and program execution (Phys. Rev. E, September 11) by Thomas Fischbacher

Evolution

- Megabase-scale human genome rearrangement with programmable bridge recombinases (Science, September 25) by Nicholas T. Perry, Liam J. Bartie, Dhruva Katrekar, Gabriel A. Gonzalez, Matthew G. Durrant, James J. Pai, Alison Fanton, Juliana Q. Martins, Masahiro Hiraizumi, Chiara Ricci-Tam, Hiroshi Nishimasu, Silvana Konermann, and Patrick D. Hsu

- Transposable elements are vectors of recurrent transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (Science, September 18) by Pierre Baduel, Louna de Oliveira, Erwann Caillieux, Grégoire Bohl-Viallefond, Ciana Xu, Mounia El Messaoudi, Aurélien Petit, Maëva Draï, Matteo Barois, Vipin Singh, Alexis Sarazin, Felipe K. Teixeira, Martine Boccara, Elodie Gilbault, Antoine de France, Leandro Quadrana, Olivier Loudet, and Vincent Colot

- Naiavirus: an enveloped giant virus with a pleomorphic, flexible tail (Nature Communications, September 17) by Matheus Rodrigues, Victória Queiroz, Thalita Arantes, Henrique Limborço, Bruna Neiva, Nidia Arias, Talita Machado, Matheus Barcelos, Juliana R. Cortines, Otavio Henrique Thiemann, Rafael Elias Marques, Talita Diniz Melo-Hanchuk, Eliana Leonor Hurtado Celis, João Pessoa Araujo Jr, Erik Reis, Luiz Carlos Junior Alcantara, Cezar Batista Cunha Santos, Abdeali Jivaji, Rodrigo A. L. Rodrigues, Frank O. Aylward, and Jônatas Santos Abrahão

Development and Patterns

- 3D pattern formation of a protein–membrane suspension (PNAS, September 12) by Amélie Chardac, Michael M. Norton, Jonathan Touboul, and Guillaume Duclos

Ecosystems

- Stabilization of macroscopic dynamics by fine-grained disorder in many-species ecosystems (Phys. Rev. E, September 4) by Juan Giral Martínez, Silvia De Monte, and Matthieu Barbier

- A theoretical framework for scaling ecological niches from individuals to species (PNAS, August 29) by Muyang Lu, Scott W. Yanco, Ben S. Carlson, Kevin Winner, Jeremy M. Cohen, Diego Ellis-Soto, Shubhi Sharma, Will Rogers, and Walter Jetz

Physics

- Turbulence without Walls: Whither the Zeroth Law of Turbulence? (Phys. Rev. Lett., September 22) by Kartik P. Iyer, Theodore D. Drivas, Gregory L. Eyink, and Katepalli R. Sreenivasan.

- Critical exponents of the spin-glass transition in a field at zero temperature (PNAS, September 10) by Maria Chiara Angelini, Saverio Palazzi, Giorgio Parisi, and Tommaso Rizzo

- Optimal transitions between nonequilibrium steady states (PNAS, September 15) by Samuel Monter, Sarah A. M. Loos, and Clemens Bechinger

Information and Computation

- Toward a unified taxonomy of information dynamics via Integrated Information Decomposition (PNAS, September 22) by Pedro A. M. Mediano, Fernando E. Rosas, Andrea I. Luppi, Robin L. Carhart-Harris, Daniel Bor, Anil K. Seth, and Adam B. Barrett

- What does it mean for a system to compute? (arXiv preprint, September 19) by David H. Wolpert and Jan Korbel

Society

- An exploration of basic human values in 38 million obituaries over 30 years (PNAS, August 26) by David M. Markowitz, Thomas Mazzuchi, Stylianos Syropoulos, Kyle Fiore Law, and Liane Young

- Universal Model of Urban Street Networks (Phys. Rev. Lett., September 25) by Marc Barthelemy and Geoff Boeing.

- Sociohydrodynamics: Data-driven modeling of social behavior (PNAS, August 29) by Daniel S. Seara, Jonathan Colen, Michel Fruchart, Yael Avni, David G. Martin, and Vincenzo Vitelli

Brain and Cognition

- Polygenic and developmental profiles of autism differ by age at diagnosis (Nature, October 1) by Xinhe Zhang, Jakob Grove, Yuanjun Gu, Cornelia K. Buus, Lea K. Nielsen, Sharon A. S. Neufeld, Mahmoud Koko, Daniel S. Malawsky, Emma M. Wade, Ellen Verhoef, Anna Gui, Laura Hegemann, APEX Consortium, iPSYCH Autism Consortium, PGC-PTSD Consortium, Daniel H. Geschwind, Naomi R. Wray, Alexandra Havdahl, Angelica Ronald, Beate St Pourcain, Elise B. Robinson, Thomas Bourgeron, Simon Baron-Cohen, Anders D. Børglum, Hilary C. Martin, and Varun Warrier

- Novelty as a drive of human exploration in complex stochastic environments (PNAS, September 25) by Alireza Modirshanechi, Wei-Hsiang Lin, He A. Xu, Michael H. Herzog, and Wulfram Gerstner

- Neural basis of cooperative behavior in biological and artificial intelligence systems (Science, September 25)by Mengping Jiang, Linfan Gu, Mingyi Ma, Qin Li, Jonathan C. Kao, and Weizhe Hong

- Temporal integration in human auditory cortex is predominantly yoked to absolute time (Nature Neuroscience, September 18) by Sam V. Norman-Haignere, Menoua Keshishian, Orrin Devinsky, Werner Doyle, Guy M. McKhann, Catherine A. Schevon, Adeen Flinker, and Nima Mesgarani

Artificial Intelligence

- A law of next-token prediction in large language models (Phys. Rev. E, September 24) by Hangfeng He and Weijie J. Su

- Are Neural Networks Collision Resistant? (arXiv preprint, September 24) by Marco Benedetti, Andrej Bogdanov, Enrico M. Malatesta, Marc Mézard, Gianmarco Perrupato, Alon Rosen, Nikolaj I. Schwartzbach, and Riccardo Zecchina

- Delegation to artificial intelligence can increase dishonest behaviour (Nature, September 17) by Nils Köbis, Zoe Rahwan, Raluca Rilla, Bramantyo Ibrahim Supriyatno, Clara Bersch, Tamer Ajaj, Jean-François Bonnefon, and Iyad Rahwan

- Against the Uncritical Adoption of 'AI' Technologies in Academia (Zenodo preprint, September 5) by Olivia Guest, Marcela Suarez, Barbara Müller, Edwin van Meerkerk, Arnoud Oude Groote Beverborg, Ronald de Haan, Andrea Reyes Elizondo, Mark Blokpoel, Natalia Scharfenberg, Annelies Kleinherenbrink, Ileana Camerino, Marieke Woensdregt, Dagmar Monett, Jed Brown, Lucy Avraamidou, Juliette Alenda-Demoutiez, Felienne Hermans and Iris van Rooij

Robotics

- A geometric condition for robot-swarm cohesion and cluster–flock transition (PNAS, September 8) by Mathias Casiulis, Eden Arbel, Charlotte van Waes, Yoav Lahini, Stefano Martiniani, Naomi Oppenheimer, and Matan Yah Ben Zion

- Route-centric ant-inspired memories enable panoramic route-following in a car-like robot (Nature Communications, September 24) by Gabriel G. Gattaux, Antoine Wystrach, Julien R. Serres, and Franck Ruffier

Just for Fun

- New dinosaur just dropped: A domed pachycephalosaur from the early Cretaceous of Mongolia (Nature, September 17, 2025) by Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig, Ryuji Takasaki, Junki Yoshida, Ryan T. Tucker, Batsaikhan Buyantegsh, Buuvei Mainbayar, Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar, and Lindsay E. Zanno

- The origins of

beerbarley: A haplotype-based evolutionary history of barley domestication (Nature, September 24) by Yu Guo, Murukarthick Jayakodi, Axel Himmelbach, Erez Ben-Yosef, Uri Davidovich, Michal David, Anat Hartmann-Shenkman, Mordechai Kislev, Tzion Fahima, Verena J. Schuenemann, Ella Reiter, Johannes Krause, Brian J. Steffenson, Nils Stein, Ehud Weiss, and Martin Mascher - Hands evolved from butts? Co-option of an ancestral cloacal regulatory landscape during digit evolution (Nature, September 17) by Aurélie Hintermann, Christopher C. Bolt, M. Brent Hawkins, Guillaume Valentin, Lucille Lopez-Delisle, Madeline M. Ryan, Sandra Gitto, Paula Barrera Gómez, Bénédicte Mascrez, Thomas A. Mansour, Tetsuya Nakamura, Matthew P. Harris, Neil H. Shubin, and Denis Duboule

- Ice Age smoked mummies: Earliest evidence of smoke-dried mummification: More than 10,000 years ago in southern China and Southeast Asia (PNAS, September 15) by Hsiao-chun Hung, Zhenhua Deng, Yiheng Liu, Zhiyu Ran, Yue Zhang, Zhen Li, Yousuke Kaifu, Qiang Huang, Khanh Trung Kien Nguyen, Hai Dang Le, Guangmao Xie, Anh Tuan Nguyen, Mariko Yamagata, Truman Simanjuntak, Sofwan Noerwidi, Mohammad Ruly Fauzi, Marlin Tolla, Alpius Wetipo, Gang He, Junmei Sawada, Chi Zhang, Peter Bellwood, and Hirofumi Matsumura

Thanks for reading! It's thanks to patrons like you that I can continue writing R2. You can help even more by sharing this post with a friend, leaving a comment, or dropping a tip in my tip jar.