Paper Roundup October 2025: dark matter, emergence, and dinosaur mummies

Papers on big questions at the frontiers of science, curated by hand each month

Every month, I publish a curated list of fascinating, groundbreaking inflammatory, or otherwise bold new scholarship on "big questions" at the frontiers of science. Inclusion is not endorsement. Think something should be included in next month's paper roundup? Shoot me an email at elise@reviewertoo.com.

If you liked this newsletter, why not share it with a friend or post it on Bluesky or wherever else you hang out online? That's the best way to help this project continue!

Don't miss next month's newsletter!

Highlights

Did we just spot a tiny blob of dark matter?

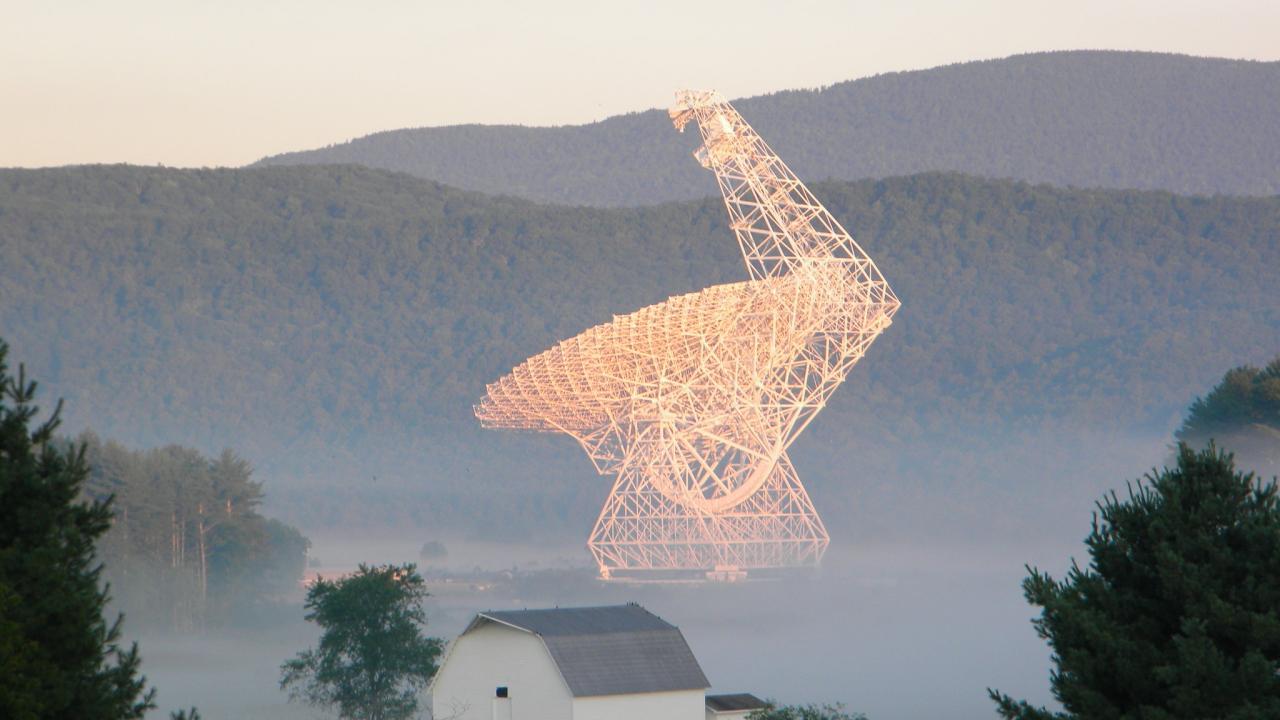

A million-solar-mass object detected at a cosmological distance using gravitational imaging (Nature Astronomy, October 9) by D. M. Powell, J. P. McKean, S. Vegetti, C. Spingola, S. D. M. White, and C. D. Fassnacht

A tiny twist in an already-twisted image of a distant galaxy might be a little blob of dark matter. The blob is about 1 million times as massive as the sun. If it is a lump of dark matter, that would be small — 100 times smaller than the smallest dark object found before. But it might also be a stealthy dwarf galaxy. If researchers can find more of these little dark blobs, it could help scientists figure out what dark matter actually is.

Dark matter is "dark" because it doesn't interact with light. But it does make itself known via another force: gravity. Scientists think it must exist because if it didn't, plenty of things we can directly observe wouldn't make sense, especially when it comes to the structure and behavior of galaxies. Gravitational lensing — the way gravity warps light — can also reveal dark matter. When something massive sits between our telescopes and a distant light source, its gravity warps our view. So by measuring the geometry of the warped source, we can infer thins about the mass in-between — even if we can't see it at all.

In this study, researchers used radio telescopes from all around the world to scrutinize a smeared-out, gravitationally lensed galaxy. And in that smeared-out light, they found an extra little kink: the gravitational fingerprint of a mysterious dark object about 1 million times the mass of our Sun. That might sound big, but the mystery blob is the smallest dark object observed yet.

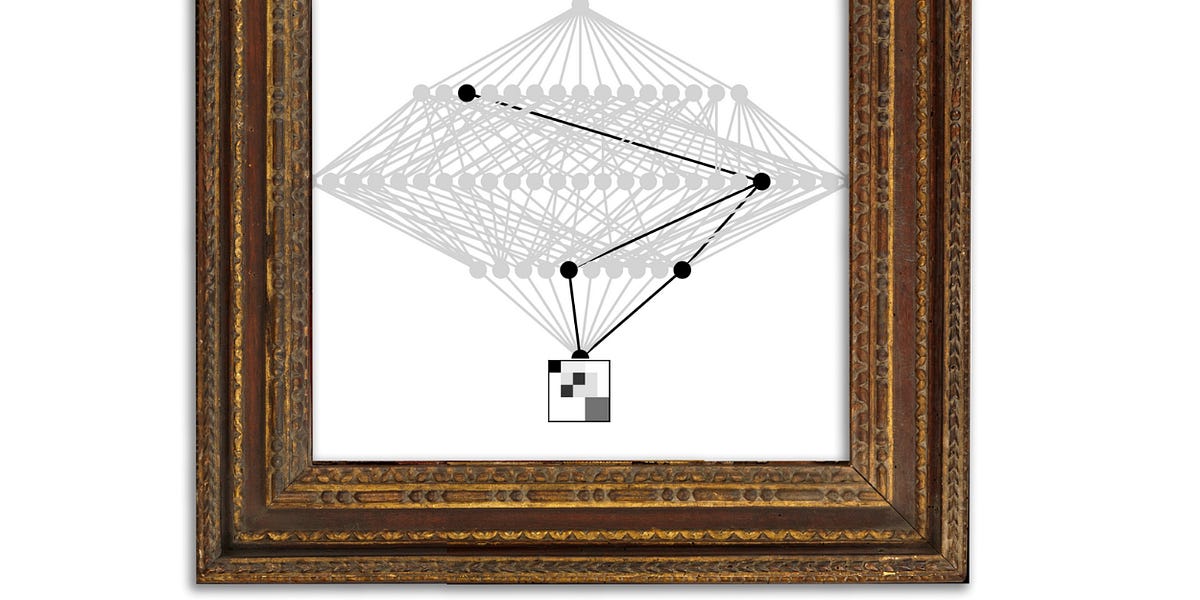

Engineering (causal) emergence

Engineering Emergence (arXiv preprint, October 3) by Abel Jansma and Erik Hoel

Emergence is one of those words that everyone uses and nobody has a good definition for — at least, not a scientific definition wrapped up in mathematics. That's starting to change. Over the past decade or so, several researchers have made some very interesting attempts to define emergence in useful terms. You might have expected this kind of work to come out of the complexity science community. But interestingly, that's not what happened. Rather, it's consciousness researchers — think people like Anil Seth and colleagues — who are doing the hard thinking on emergence lately. And that includes Erik Hoel, who helped develop the integrated information theory of consciousness before borrowing parts of IIT for a new theory of emergence.

Hoel introduced his "causal emergence" theory 8 years ago — for a crash course, see Natalie Wolchover's 2017 Quanta piece. Now, after a hiatus from science, Hoel is back with new work that claims to address several common criticisms of causal emergence and expands the framework in interesting new ways. This is the second paper in that effort.

To me, the title "Engineering emergence" obscures this paper's most interesting contribution to discourse around complexity and emergence: defining complexity in terms of emergence. Hoel essentially provides a) a way to identify (or engineer) macroscale levels (coarse-grainings) of a system that could reasonably be considered "emergent" because of their causal properties and then b) encourages us to think about systems as having an architecture of emergent levels. A more complex system has more emergent macroscales — milk swirling into coffee is more complex than thoroughly-mixed coffee because there are more scales at which it is causally emergent. I like this, because it puts the idea of "multi-scale organization" or "heierarchies of scale" as a hallmark of complex systems on firm theoretical footing. We can do better than a nesting doll metaphor.

Of course, I'm a layperson who can't dig into the math myself. So take my impressions with a hefty grain of salt. I haven't had the chance to speak with many experts about causal emergence yet, but my impression is that it hasn't really caught on in the complexity community. I'd love to know why.

For those interested in digging deeper, Hoel wrote a plain-language walkthrough of the paper on his Substack:

Islands of dreamless sleep

Hemispherotomy leads to persistent sleep-like slow waves in the isolated cortex of awake humans (PLOS Biology, October 16, 2025) by Michele Angelo Colombo, Jacopo Favaro, Ezequiel Mikulan, Andrea Pigorini, Flavia Maria Zauli, Ivana Sartori, Piergiorgio d’Orio, Laura Castana, Irene Toldo, Stefano Sartori, Simone Sarasso, Tim Bayne, Anil K. Seth, and Marcello Massimini.

Speaking of the consciousness community, one of the more interesting things to have come out of it in recent years is a set of quantitative measurements correlated with consciousness. These have allowed scientists to, among other things, realize that an alarmingly high percentage (something like 20%!) of patients who appear to be in a coma or otherwise totally unresponsive — basically, people who look dead to the outside world — are still conscious. Researchers also have a much better hold on the types of brain activity patterns associated with stakes like wakefulness and sleep.

This study uses those tools to ask a frankly disturbing question: could a brain hemisphere that's been entirely cut off from the world still conscious?

If so, that'd mean there are people walking around with around trapped, locked-in second consciousnesses in their skulls. Some kids with severe epilepsy undergo a procedure called hemispherotomy that almost entirely severs one brain hemisphere from the rest of the body. This surgery goes far beyond the more famous split-hemisphere procedure, which prevents the left and right hemispheres from talking to each other but otherwise keeps them intact. It severs one hemisphere entirely from sensory and motor pathways. Basically, it's hooked up to blood vessels but basically nothing else. It not only cannot communicate with the other hemisphere, it cannot act or perceive.

For researchers, this dramatic procedure is a chance to look for "islands of awareness" — loci of conscious experience cut off from the world. Is it even possible to be conscious without having a world to interact with? Considering how central world modeling is to several lines of thinking about consciousness, it's not unreasonable to think the answer could be "no."

This study reports "slow wave" patterns of brain activity in the isolate hemispheres of hemispherotomy patients that look quite a bit like those seen in dreamless sleep or sedation. Slow waves don't always mean someone is unconscious. But they're a good hit — good enough, at least, to be used in clinical settings to adjust anesthesia during surgery and to judge how conscious unresponsive patients might be.

I find this, somehow, reassuring. It's not conclusive evidence that the isolated hemisphere essentially goes to sleep. But it does show that the isolated hemisphere is clearly in a different, probably less wakeful and possibly even unconscious state of being than the connected one. If the isolated hemisphere is conscious at all, I wonder if it would become hyper-aware of the limited input it does receive from the outside world via the blood. What would it be like to inhabit a world defined only by blood sugar, blood oxygen, nutrients, hormones — and perhaps a few memories, scraps of the half-forgotten world of vivid sensory experience from before everything went black?

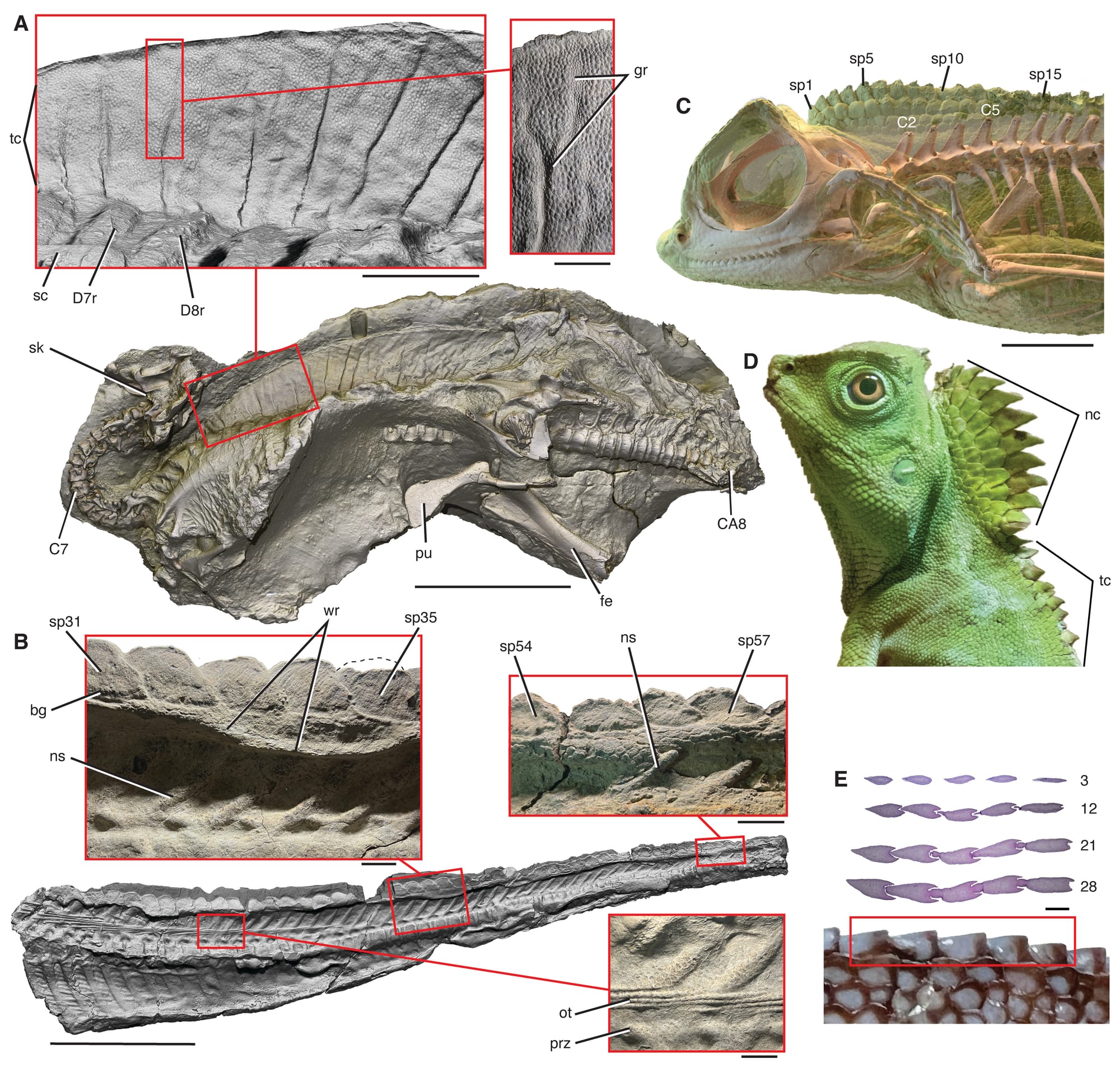

Dinosaur mummies

Duck-billed dinosaur fleshy midline and hooves reveal terrestrial clay-template “mummification” (Science, October 23) by Paul C. Sereno, Evan T. Saitta, Daniel Vidal, Nathan Myhrvold, María Ciudad Real, Stephanie L. Baumgart, Lauren L. Bop, Tyler M. Keillor, Marcus Eriksen, and Kraig Derstler

Need I really say more?

Alien topography from alien skies

Probing the geological setting of exoplanets through atmospheric analysis: Using Mars as a test case (Icarus, October 16) by Monica Rainer, Evandro Balbi, Francesco Borsa, Paola Cianfarra, Avet Harutyunyan, and Silvano Tosi.

I really do try to keep tabs on exoplanet astronomy. So I was surprised to see this paper propose something that I've literally never heard someone talk about before: using observations of a planet's atmosphere to constrain its surface topography.

Using chemicals in an exoplanet's sky to determine whether there's a mountain range or canyon down there on the ground? Sounds out-there. But the authors of this paper claim it should be feasible and use Mars as a test case. The core idea is sounds quite clever. The strength of the spectral "fingerprints" of chemicals in a planet's atmosphere can depend on the thickness of the atmosphere. So seeing weaker fingerprints in some patches compared to others might hint at different topography. Being able to do this for exoplanets at all hinges on future telescopes that could make spatially-resolved observations of the compositions of exoplanet atmospheres, which we're quite far away from. I just find this a fun idea and love that people are trying to be this creative about squeezing as much information about planets out of very, very limited observations.

Linguistic side-note: this paper uses the jargon word "telluric planet" instead of "terrestrial planet" and I am truly at a loss for why. I have never once heard that term before and don't see what advantage it has over terrestrial. Leave a comment if you know what's going on here!

It took us until 2025 to...

Comparative analysis of human and mouse ovaries across age (Science, October 9) by Eliza A. Gaylord, Mariko H. Foecke, Ryan M. Samuel, Bikem Soygur, Angela M. Detweiler, Tara I. McIntyre, Leah C. Dorman, Michael Borja, Amy E. Laird, Ritwicq Arjyal, Juan Du, James M. Gardner, Norma Neff, Faranak Fattahi, and Diana J. Laird

... get serious about matching up the biology of human ovaries to mouse ovaries. For context, mice and rats are the go-to model organisms for studying reproductive aging, even though they don't go through menopause like humans do (to be fair, few animals do).

This honestly seems like something we should have figured out a decade ago. But here we are.

A special issue on origins of life

Theme issue: ‘Origins of life: the possible and the actual’ (Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, October 2) compiled by Ricard Solé, Chris Kempes and Susan Stepney

Lots of origin of life papers this month! Instead of listing out every paper in this special issue below, I just want to link to the collection here. Highlights include:

- A paper on the thermodynamics of Darwinian selection on molecules by Artemy Kolchinsky

- A review of efforts to make living computer programs by Susan Stepney

- A review on phase transitions in the origins of life by Ricard Solé (a leading expert on phase transitions in complexity) and Manilo Domenico.

- A theoretical look at how hard it is to keep cells wrapped in a membrane by Chris Kempes, Diana Avila, and Cole Mathis (whose name you might recognize from my post last month on the recent Mars biosignature claim)

Don't miss the next paper roundup! Subscribe to R2 to stay on top of the biggest ideas in astrobiology, origins of life, and complexity science.

The Rest

The Universe

- Evidence for small-scale torsional Alfvén waves in the solar corona (Nature Astronomy, October 24) by R. J. Morton, Y. Gao, E. Tajfirouze, H. Tian, T. Van Doorsselaere, and T. A. Schad

Planets and Habitability

- Building wet planets through high-pressure magma–hydrogen reactions (Nature, October 29) by H. W. Horn, A. Vazan, S. Chariton, V. B. Prakapenka, and S.-H. Shim

- Horizontal and vertical exoplanet thermal structure from a JWST spectroscopic eclipse map (Nature Astronomy, October 28) by Ryan C. Challener, Megan Weiner Mansfield, Patricio E. Cubillos, Anjali A. A. Piette, Louis-Philippe Coulombe, Hayley Beltz, Jasmina Blecic, Emily Rauscher, Jacob L. Bean, Björn Benneke, Eliza M.-R. Kempton, Joseph Harrington, Thaddeus D. Komacek, Vivien Parmentier, and Xi Zhang

- Planetary Albedo Is Limited by the Above-cloud Atmosphere: Implications for Sub-Neptune Climates (The Astrophysical Journal, October 28) by Sean Jordan, Oliver Shorttle, and Sascha P. Quanz

- The Influence of Tidal Heating on the Habitability of Planets Orbiting White Dwarfs (The Astrophysical Journal Letters, October 21) by Juliette Becker, Darryl Z. Seligman, Fred C. Adams, and Marshall J. Styczinski.

- Exomoons of Circumbinary Planets (arXiv preprint, October 15, 2025 revision) by Ben R. Gordon, Helena Buschermöhle, Wata Tubthong, David V. Martin, Sean Smallets, Grace Masiello, and Liz Bergeron.

- Solar Hegemony: M-Dwarfs Are Unlikely to Host Observers Such as Ourselves (arXiv preprint, September 19) by David Kipping

Earth

- Destabilization of Earth system tipping elements (Nature Geoscience, October 1) by Niklas Boers, Teng Liu, Sebastian Bathiany, Maya Ben-Yami, Lana L. Blaschke, Nils Bochow, Chris A. Boulton, Timothy M. Lenton, Andreas Morr, Da Nian, Martin Rypdal, and Taylor Smith

Biosignatures and SETI

- A Cost-Effective Search for Extraterrestrial Probes in the Solar System (arXiv preprint, October 19) by Beatriz Villarroel, Wesley A. Watters, Alina Streblyanska, Enrique Solano, Stefan Geier, and Lars Mattsson

- Detection of organic compounds in freshly ejected ice grains from Enceladus’s ocean (Nature Astronomy, October 1) by Nozair Khawaja, Frank Postberg, Thomas R. O’Sullivan, Maryse Napoleoni, Sascha Kempf, Fabian Klenner, Yasuhito Sekine, Maxwell Craddock, Jon Hillier, Jonas Simolka, Lucía Hortal Sánchez, and Ralf Srama

Origins and Artificial Life

- Amides from the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu: nanoscale spectral and isotopic characterizations (arXiv preprint, October 29) by L. G. Vacher, V. T. H. Phan, L. Bonal, M. Iskakova, O. Poch, P. Beck, E. Quirico, and R. C. Ogliore

- A stoichiometric selection advantage of DNA genomes over RNA genomes (bioRxiv preprint, October 22) by Rosemary Yu

- GTP before ATP: The energy currency at the origin of genes (arXiv preprint, October 9) by Natalia Mrnjavac and William F. Martin

- A scope of prebiotic neat reaction conditions and the mechanism of urea-assisted phosphorylations of alcohols (Nature Communications, October 8) by Anastasiia Shvetsova, Lynda Merzoud, Augustin Lopez, Elodie Fromentin, Anne Baudouin, Henry Chermette, Isabelle Daniel, Michele Fiore, and Peter Strazewski

Evolution

- Evidence for improved DNA repair in long-lived bowhead whale (Nature, October 29) by Denis Firsanov, Max Zacher, Xiao Tian, Todd L. Sformo, Yang Zhao, Gregory Tombline, J. Yuyang Lu, Zhizhong Zheng, Luigi Perelli, Enrico Gurreri, Li Zhang, Jing Guo, Anatoly Korotkov, Valentin Volobaev, Seyed Ali Biashad, Zhihui Zhang, Johanna Heid, Alexander Y. Maslov, Shixiang Sun, Zhuoer Wu, Jonathan Gigas, Eric C. Hillpot, John C. Martinez, Minseon Lee, Alyssa Williams, Abbey Gilman, Nicholas Hamilton, Ekaterina Strelkova, Ena Haseljic, Avnee Patel, Maggie E. Straight, Nalani Miller, Julia Ablaeva, Lok Ming Tam, Chloé Couderc, Michael R. Hoopmann, Robert L. Moritz, Shingo Fujii, Amandine Pelletier, Dan J. Hayman, Hongrui Liu, Yuxuan Cai, Anthony K. L. Leung, Zhengdong Zhang, C. Bradley Nelson, Lisa M. Abegglen, Joshua D. Schiffman, Vadim N. Gladyshev, Carlo C. Maley, Mauro Modesti, Giannicola Genovese, Mirre J. P. Simons, Jan Vijg, Andrei Seluanov, and Vera Gorbunova

- Emergence of antiphage functions from random sequence libraries reveals mechanisms of gene birth (PNAS, October 15) by Idan Frumkin, Christopher N. Vassallo, Yi Hua Chen, and Michael T. Laub

- How to upgrade stolen organelles into permanent plastids: A comparative transcriptomic perspective (PNAS, September 30) by Norico Yamada, Richard G. Dorrell, Ugo Cenci, Peter G. Kroth, Vincent Lombard, and Brittany N. Sprecher

- Engineered geminivirus replicons enable rapid in planta directed evolution (Science, October 2) by Haocheng Zhu, Xu Qin, Leyan Wei, Dandan Jiang, Qiao Zhang, Wenqian Wang, Ronghong Liang, Rui Zhang, Kang Zhang, Guanwen Liu, Kevin Tianmeng Zhao, Kunling Chen, Jin-Long Qiu, and Caixia Gao,.

Physics and Chemistry

- Classical theories of gravity produce entanglement (Nature, October 22) by Joseph Aziz and Richard Howl

- A framework for the use of generative modelling in non-equilibrium statistical mechanics (arXiv preprint, October 14) by Karl J Friston, Maxwell J D Ramstead, and Dalton A R Sakthivadivel

- When Aggregation Becomes the Norm: Interpreting Experiments Beyond Their Molecules (ChemRxiv preprint, October 14, 2025, Version 1) by Alex Blokhuis, Yannick Geiger, and Sijbren Otto

Information and Computation

- Observation of constructive interference at the edge of quantum ergodicity (Nature, October 22) by Google Quantum AI and Collaborators

- Mind the gaps: The fraught road to quantum advantage (arXiv preprint, October 22) by Jens Eisert and John Preskill

- Entanglement theory with limited computational resources (Nature Physics, October 22) by Lorenzo Leone, Jacopo Rizzo, Jens Eisert, and Sofiene Jerbi

- When Maxwell’s Demon Leaves the Room (BioSystems, October 14) by P.G. Tello and S. Kauffman

- Self-replication and Computational Universality (arXiv preprint, October 9) by Jordan Cotler, Clément Hongler, and Barbora Hudcová

Biological Self-Organization

- Allocentric flocking (Nature Communications, October 13) by Mohammad Salahshour and Iain D. Couzin

- Identification of brain-like complex information architectures in embryonic tissue of Xenopus laevis organoids (Organogenesis, October 7) by Thomas F. Varley, Vaibhav P. Pai, Caitlin Grasso, Jeantine Lunshof, Michael Levin, and Josh Bongard

Society

- The Anatomy of Blame: A Network Analysis of Strategic Responsibility-Shifting After a Systemic Disaster (arXiv, October 24) by Mariano Devoto and Pablo Ariel Cipriotti

- The Physics of News, Rumors, and Opinions (arXiv preprint, October 16) by Guido Caldarelli, Oriol Artime, Giulia Fischetti, Stefano Guarino, Andrzej Nowak, Fabio Saracco, Petter Holme, and Manlio de Domenico

- Electing amateur politicians reduces cross-party collaboration (PNAS, October 9) by Rachel Porter, Jeffrey J. Harden, and Mackenzie R. Dobson

- High rates of polygyny do not lock large proportions of men out of the marriage market (PNAS, October 3) by Hampton Gaddy, Rebecca Sear, and Laura Fortunato

- The distinctive innovation patterns and network embeddedness of scientific prizewinners (PNAS, September 29) by Chaolin Tian, Yurui Huang, Ching Jin, Yifang Ma, and Brian Uzzi

Brain and Cognition

- Simultaneous EEG-PET-MRI identifies temporally coupled and spatially structured brain dynamics across wakefulness and NREM sleep (Nature Communications, October 24) by Jingyuan E. Chen, Laura D. Lewis, Sean E. Coursey, Ciprian Catana, Jonathan R. Polimeni, Jiawen Fan, Kyle S. Droppa, Rudra Patel, Hsiao-Ying Wey, Catie Chang, Dara S. Manoach, Julie C. Price, Christin Y. Sander, and Bruce R. Rosen

- Hierarchical dynamic coding coordinates speech comprehension in the human brain (PNAS, October 17) by Laura Gwilliams, Alec Marantz, David Poeppel, and Jean-Rémi King

- Nonequilibrium Physics of Brain Dynamics (arXiv preprint, October 16) by Ramón Nartallo-Kaluarachchi, Morten L. Kringelbach, Gustavo Deco, Renaud Lambiotte, and Alain Goriely.

- Neural correlates of perceptual consciousness from within: a narrative review of human intracranial research (arXiv preprint, October 9) by Francois Stockart, Alexis Robin, Hal Blumenfeld, Milan Brazdil, Philippe Kahane, Liad Mudrik, Jasmine Thum, Michael Pereira, and Nathan Faivre

Robotics and Artificial Life

- Ultrasound-driven programmable artificial muscles (Nature, October 29) by Zhan Shi, Zhiyuan Zhang, Justus Schnermann, Stephan C. F. Neuhauss, Nitesh Nama, Raphael Wittkowski, and Daniel Ahmed

Philosophy of Science

- Bet on functionalism (PhilPapers preprint, October 24) by Matthias Michel

- Agency Cannot Be a Purely Quantum Phenomenon (arXiv preprint, October 15) by Emily C. Adlam, Kelvin J. McQueen, and Mordecai Waegell.

Just for Fun

- Cold-pressed black holes: Black Hole Cold Brew: Fermi Degeneracy Pressure (arXiv preprint, October 28) by Wei-Xiang Feng, Hai-Bo Yu, and Yi-Ming Zhong

- Birds with old man voice: Voice Changes in Aging Birdsong: A Longitudinal Study in Adult Male Zebra Finches (bioRxiv preprint, October 27) by Michelle L. Gordon, Arpita Gulati, Robin A. Samlan, and Julie E. Miller

- Ideal stalagmite shapes: Shapes of ideal stalagmites (PNAS, October 16) by Piotr Szymczak, Anthony J. C. Ladd, Matej Lipar, and Dean Pekarovič

- The physics of optimal onion cutting: Droplet outbursts from onion cutting (PNAS, October 7) by Zixuan Wu, Alireza Hooshanginejad, Weilun Wang, Chung-Yuen Hui, and Sunghwan Jung

- Micolightning sparks will-o'-the-wisps: Unveiling ignis fatuus: Microlightning between microbubbles (PNAS, September 29) by Yu Xia, Yifan Meng, Jianbo Shi, and Richard N. Zare

Thanks for reading! It's thanks to patrons like you that I can continue writing R2. You can help even more by sharing this post with a friend, leaving a comment, or dropping a tip in my tip jar.