A bad month for space whales

Two new papers on Europa and Titan complicate the case for habitable oceans on the icy moons. They're still our best bet for finding aliens.

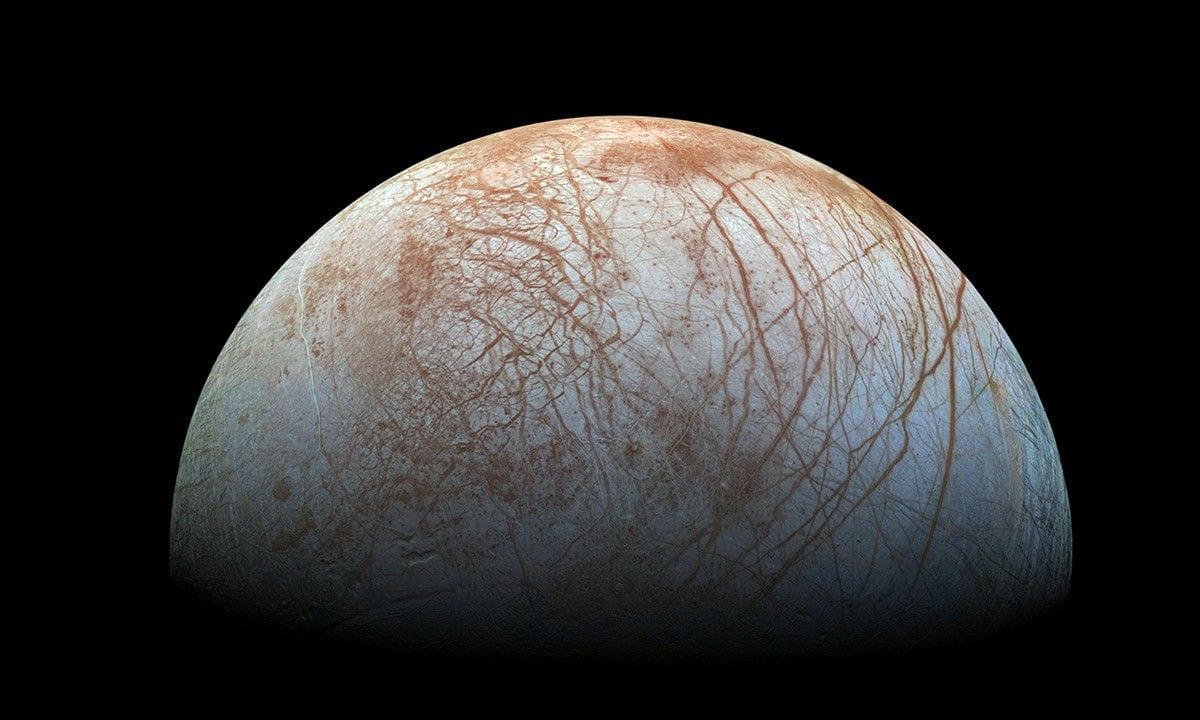

Beneath the icy crust of Jupiter's moon Europa lies a ocean of liquid water. This dark alien sea is thought to be between 60 and 150 kilometers deep — up to 10 times deeper than even the deepest ocean trenches on Earth — and contains more liquid water than all of Earth's oceans combined.

Compared to Mars — a toxic, dusty, irradiated ball of dry dirt with almost no atmosphere to speak of — and Venus, which somehow manages to be even more hellish, an enormous ocean wrapped up in a protective icy shell sounds pretty hospitable. It's hard not to leap into flights of fancy: forests of weird, bioluminescent Europan kelp swaying on the currents, alien squids, space whales, it's all just too fun to imagine. But there's an element of fact to this fantasy, at least in that astrobiologists genuinely consider Europa and the other icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn to be among most promising places to look for life in our solar system.

So it's a bit concerning that two papers came out this past month that complicate hopes for subsurface ocean biospheres on the icy moons we're about to visit and study in the greatest detail — Europa and Saturn's moon Titan. Europa's ocean could be tectonically and geochemically dead, which would mean there'd be little energy available for a potential biosphere. And Titan might not have a liquid water ocean at all.

Europa's ocean could be geologically dead

The first images of Jupiter's moon Europa beamed back by the Voyager 1 and 2 probes hinted at a subsurface ocean: the icy sphere was crisscrossed with cracks, but almost no impact craters. That'd make sense if the moon had a kind of icy plate tectonics, with a mantle of liquid water beneath a jigsaw of icy plates. And in the 1990s, the Galileo mission confirmed what researchers had long suspected: Europa's icy crust concealed an ocean of salty water.

But water alone isn't enough for biology. To make a living, life needs energy. And in Europa's dark, sun-starved ocean, there's only one possible source: geochemistry. The details can get pretty weird, but generally speaking even the most exotic lifeforms gets energy by breathing and eating — and on Europa, the edible stuff comes from the moon's interior and the breatheable stuff comes from the surface and gets dumped into the ocean by Europa's weird icy plate tectonics. Mixing the two together — for instance, at a deep-sea hydrothermal spring — make chemical energy available to life.

To sustain a biosphere, Europa would need some way of continuously exposing fresh material from its insides to its ocean water so this mixing can keep going. No mixing, no interesting geochemistry, no life.

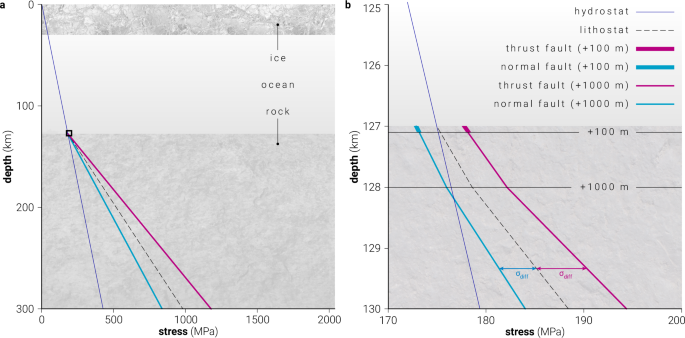

Previously researchers thought racks and faults in Europa's seafloor could expose fresh rock from the interior to ocean water. But in a January 6 paper in Nature Communications, Paul Byrne and his colleagues showed that Europa's rocky interior probably doesn't crack and fault at all. Not even along its weakest points. And without cracks, fluids from Europa's ocean probably can only circulate through the uppermost hundred meters or so of the seafloor.

If they're right, the moon may have run out of "food" very quickly. It's that's true, massive ocean could be a lifeless, watery desert.

Titan could have no ocean at all

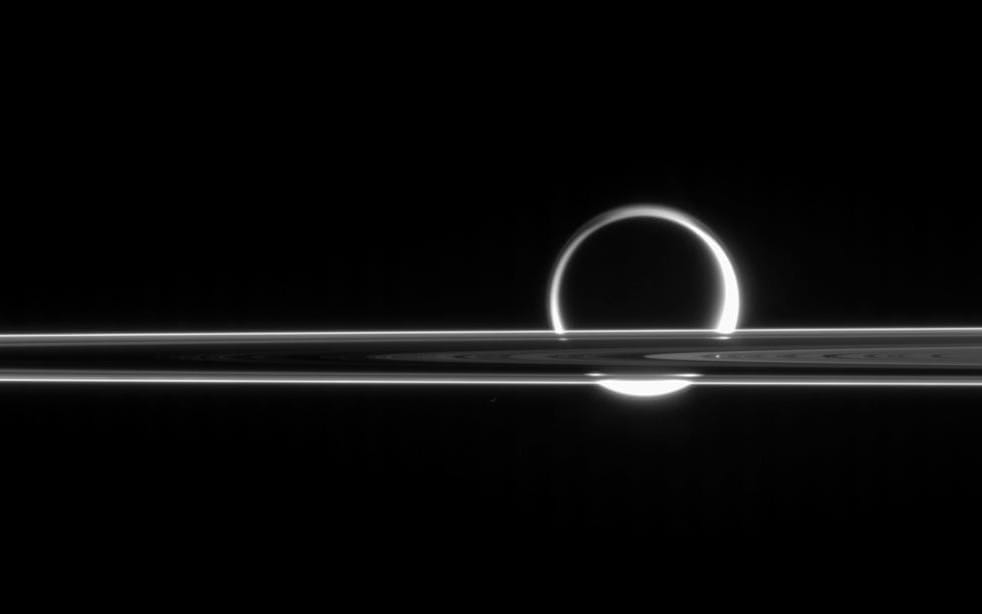

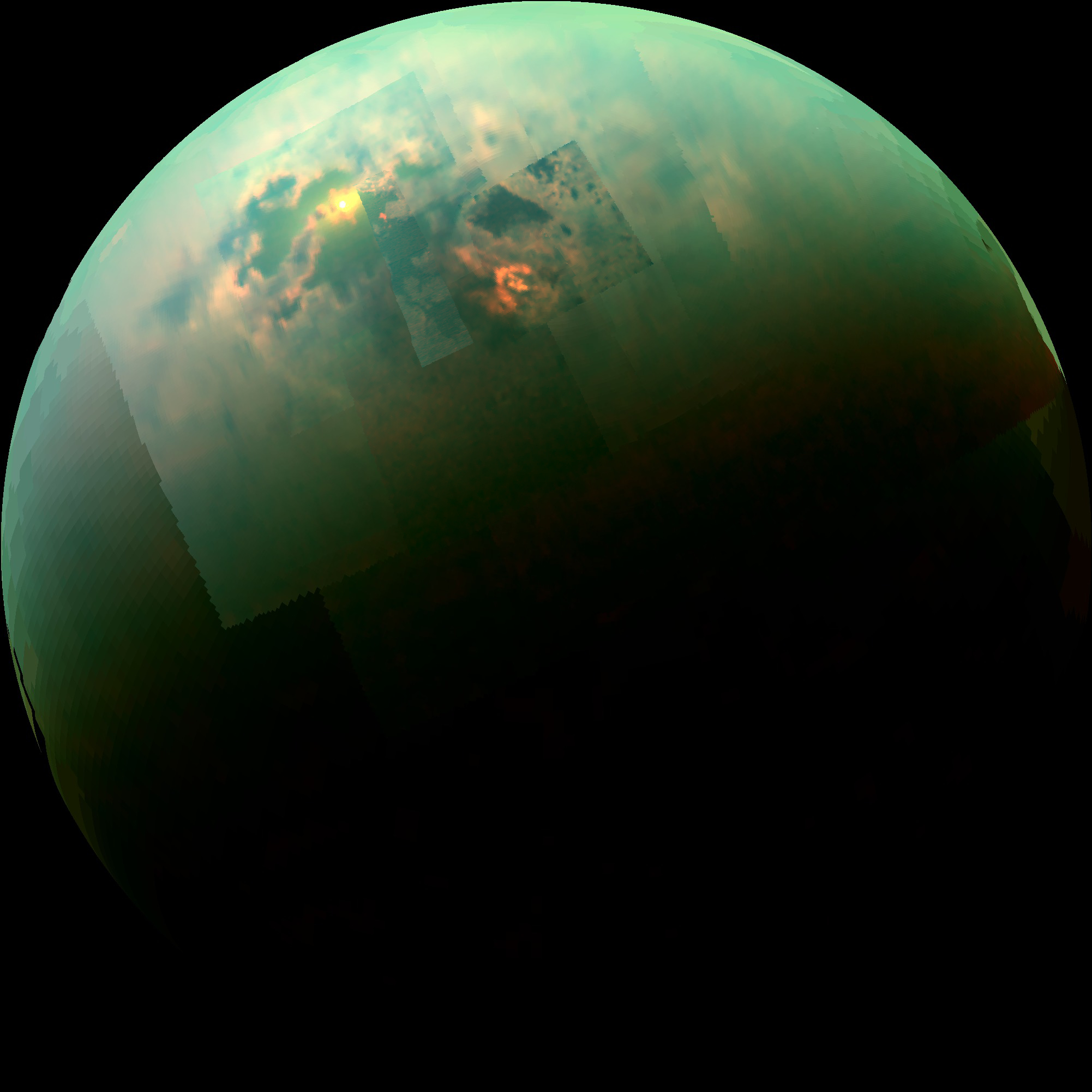

Saturn's moon Titan is maybe even more interesting than Europa: it is the only place in the solar system other than Earth that has rain, rivers, and lakes. Except this frosty moon is so cold that its rock is frozen water, and its "water" is liquid methane and ethane. And to make matters more interesting, the moon's surface and atmosphere are absolutely overflowing with organic molecules formed through reactions with sunlight and energetic particles flung by Saturn's magnetic field into the moon's thick atmosphere.

Titan's strange surface has long inspired speculation about finding life-as-we-don't-know-it that uses liquid methane or ethane in place of water. But Titan could have an ocean of liquid water below its icy crust, too. Unlike Europa's ocean, this ocean wouldn't be in direct contact with rock — it's seafloor would be a weird, high-pressure ice phase — and that already complicates the habitability picture since it'd get in the way of geochemistry that could sustain life. But still: a liquid water ocean in contact with the surface of a moon absolutely overflowing with interesting organic molecules absolutely should be at the top of our list of places to look for life in the solar system.

However, it's now looking like Titan may not have that subsurface ocean, after all.

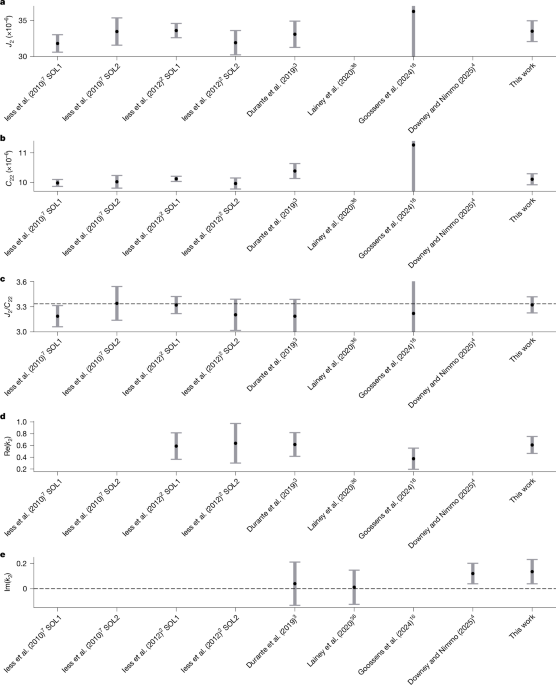

In a paper published December 17 in Nature, Flavio Petricca and colleagues analyzed Titan's gravitational field and its response to the tidal forces its endures as it whirls around Saturn and what they found is inconsistent with an ocean world. Basically, liquid and solid respond to tidal forces differently — liquid basically just sloshes around (think about Earth's tides), while solids deform and break and rub past themselves, causing friction that "dissipates" the tidal energy as heat. Researchers could determine that there's more of this tidal dissipation happening inside Titan than you'd expect from a moon full of liquid water. Instead, the team thinks that Titan has a "mushy" layer of ice that's mostly solid, but partially melted — a bit like Earth's mantle, which is mostly solid rock with the consistency of silly putty, but has molten patches.

This result concerns Titan, specifically, but could have implications for other worlds: if Titan remains solid despite receiving quite a lot of tidal heating from Saturn, that could indicate that ocean worlds are rarer that we thought.

But what about space bacteria?

So, it's not looking good for space whales.

Space microbes, though? That's another story. Microbes are tough little guys and they can endure truly crazy environments and squeeze a living out of almost any energy source. We're not hoping to find anything more complex than a microbe on Mars or Venus, either, and there's still good reason to think that Titan and Europa are the best places to look for extant life in our solar system.

The authors of the Europa paper point out that even without fracturing, there could still be sources of "food" for microbial life on Europa. This includes, wildly, production of hydrogen gas, sulfate, and even organic carbon driven by the decay of radioactive elements in the crust. As cool as it sounds, living on the byproducts of radioactive decay would be slim pickings, energetically speaking. It'd maybe be enough for some microbes, but nothing that could sustain a magnificent Europan space whale.

But hey: whales weren't really on the table, anyways. Even hydrothermal vents like we see on Earth would be pretty meager fuel for a big complex creature. I've never heard a researcher talk about anything but microbial life as a serious possibility for Europa. So this might not change the picture much. Future studies will need to work out the details to determine how much biomass Europa could support without fractures to expose fresh rock to its ocean.

And while the lack of a liquid water ocean beneath Titan is a bit disappointing, it is ultimately not that much of a blow to our hopes of finding life there. What makes Titan so tantalizing is not the chance of finding life as we know it. It's the chance of finding life as we don't know it. Titan is a weird, icy doppelgänger of Earth. The rocks are made of water, the water is made of liquified gas, and the air is a thick haze full of organic molecules. If we find something alive there, I'd honestly be disappointed if it was just another water-based cell.

Fans of water-based cells can still get excited about Titan, too, even with its newly proposed slush-ball composition. Slush pockets could even be good news for life, because they'd concentrate organic molecules and minerals in little pools where they can react and do interesting things rather than diluting in a big ocean (dilution may be the solution to pollution but it's death knell for protocells). Microbes thrive in slushy, briny pools under glaciers at the poles on Earth. And the research team behind the new study suggested that convection of slushy melts could move material that'd been in contact with Titan's rocky interior — and therefore full of interesting geochemical goodies — up to higher layers in contact with the organic-rich exterior. Briny slush pockets are no place for complex life, but they could be a great place to be a microbe.

The icy moons are still our best bet for a biosignature

Even if we are unlikely to find complex life on the icy moons, they're still — in my opinion — our best bet for finding a compelling sign of anything both alien and alive in our solar system in the near future.

We know Mars pretty well, and it looks pretty dang dead. Maybe it wasn't always dead. The whole point of sending rovers like Perseverance to Mars is to look for signs of ancient life and recently it even found a possible biosignature in a 4 billion-year old rock. But to have a shot at confirming the biosignature, we'd need to have that rock in our hands in a lab on Earth, and NASA's Mars Sample Return isn't happening. China could bring back Mars rocks, but even so: interpreting 4 billion year-old traces of microbial life is tricky stuff even on our own planet, where we know life isn't a ridiculous hypothesis.

It'd be easier to convince ourself we'd found life if we find something that's still, well, alive. An eating, excreting cell speaks for itself.

That's maybe a reason to be more interested in Venus than Mars. Even if Mars does host life today, that life would have to be buried somewhere out of reach of our instruments and robotic explorers. ESA's Rosalind Franklin rover, set to land in 2030 if all goes well, will drill a whopping 2 meters into the subsurface. That's about as deep as a tall dude is tall! I'm being a bit facetious, this rover is actually pretty dang exciting and 2 meters could be a big deal since that's deep enough to protect organic molecules from the nasty radiation on Mars' surface. It's just definitely not deep for liquid water (for that, you'd need to go 10-20 kilometers deep), so if scientists find anything it'll be billion-year-old leftovers of life that will be very hard to interpret.

On Venus, there's a cloud layer that'd be survivable for Earth life — and in 2020, researchers might have detected a hint of the stinky gas phosphine in Venus' clouds at around the right height. The detection is controversial, let alone the interpretation as a biosignature. But it'd sure be way easier to drop a probe through Venus' atmosphere and hunt for life in the clouds than to drill through Mars to look for subsurface life. Still, we're not doing that. Not soon, at least. There are several upcoming missions to Venus that are very cool and worthy of hype, only one planned would sample Venus' atmosphere — the Venus Life Finder from Rocket Lab and MIT. Its single instrument can do one thing: detect the mere presence or absence of organic molecules, which can form all over in space. It won't even be able to detect phosphine. It will not settle the life question.

What about exoplanets? They're even more of a long shot — at least for now. Scientists are optimistic that they'll eventually be able to detect atmospheres on terrestrial planets using JWST, including on temperate and cool worlds that are harder to study than the hot rocks researchers are mostly focusing on to start. But for now, just finding alien air is an ambitious goal, let alone characterizing it. We'd have a better shot for bigger planets, which is a reason some scientists are excited about hypothetical "Hycean" planets — sub-Neptune water worlds with global oceans beneath thick hydrogen atmospheres that'd be easier to characterize with JWST. But even in the best case scenario, the most we'll be able to do with telescopes (even future ones) is characterize gases at the very tippy tops of the upper atmospheres of exoplanets. Telescopes aren't life detectors, and interpreting exoplanet biosignatures is going to be really, really hard.

The icy moons, on the other hand, are great targets for the technology and missions we have right now.

Two spacecraft are already on their way to the Jovian system: NASA's Europa Clipper and ESA's JUICE. Clipper will arrive in 2030, JUICE in 2031.[1] Either probe could fly through plumes of water spewed out from Europa's icy ocean, offering a chance to sample its depths. Mars does not conveniently belch up deep subsurface material like this. We don't have to drill Europa to sample its interior ocean, which is truly an amazing opportunity to hunt for life.

Titan might be even more exciting. The Dragonfly mission — the most innovative, bold thing NASA has done since landing a rover on Mars for the first time, in my opinion — is set to arrive in 2034. It'll be a quadcopter and will fly around the moon. Cool factor aside, that means it'll be able to explore plenty of different environments, possibly including impact sites that temporarily melt water on Titan's surface and cryovolcanic flows erupting water and organic compounds from Titan's interior. Again — free interior samples! You just don't get that on Mars. Dragonfly will also be able to peer into Titan's subsurface. So pretty soon, we'll know for sure whether there's a liquid water ocean down there or just a bunch of slush.

So yeah. No space whales. Whatever. Onwards to the icy moons!

Footnotes

[1]: I just want to complain: It takes these things forever to get anywhere because they do a lot of complicated gravity assist maneuvers to save up on fuel. Just look at JUICE's flight path. Look at it. Using heftier rockets and just heading straight to Jupiter would be years faster. But it'd be super expensive.

Thanks for reading

There are many ways you can help:

- Subscribe, if you haven't already!

- Share this post on Bluesky, Twitter/X, LinkedIn, Facebook, or wherever else you hang out online.

- Become a patron for the price of 1 cappuccino per month

- Drop a few bucks in my tip jar

- Send recommendations for research to feature in my monthly paper roundups to elise@reviewertoo.com with the subject line "Paper Roundup Recommendation"

- Tell me about your research for a Q&A post (email enquiries to elise@reviewertoo.com)

- Follow me on Bluesky

- Spread the word!